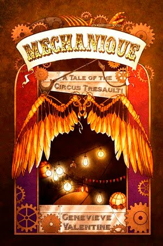

Book Review: “Mechanique: A Tale of the Circus Tresault” by Genevieve Valentine

In a time of thousand-page fantasy epics, a little book like Genevieve Valentine’s Mechanique: A Tale of the Circus Tresaulti is easy to overlook. I recommend making the effort to track it down. Mechanique is a beautifully written book. Genevieve Valentine says more with hints and suggestions than some authors can say in a thousand words of blunt narration. There is more truth in Mechanique than in other books twice its size.

In a time of thousand-page fantasy epics, a little book like Genevieve Valentine’s Mechanique: A Tale of the Circus Tresaulti is easy to overlook. I recommend making the effort to track it down. Mechanique is a beautifully written book. Genevieve Valentine says more with hints and suggestions than some authors can say in a thousand words of blunt narration. There is more truth in Mechanique than in other books twice its size.

Mechanique has been categorized “steampunk,” but it does not indulge in the Victorian nostalgia that marks the steampunk literature that I’m familiar with. The world of Mechanique is a post-war wasteland, where last scraps of civilization survive in walled cities. It is outside these cities that the Circus Tresaulti pitches its tents. Little George, the book’s first person narrator, is the circus’s advance scout, putting up posters and checking the mood of the inhabitants to see if they’re the kind of people who might enjoy a circus — or who would rather enjoy chasing a circus out of town.

The mechanical legs that Little George wears for these excursions are fake, but the core of the circus are its genuine half-mechanical performers. Women with metal bones, men with reinforced mechanical bodies, and, once, a man with mechanical wings. It sounds like a good deal — have your fragile and overheavy bones replaced with light, flexible copper and spend your days on a high-flying trapeze. The Boss doesn’t take just anyone, though, and being accepted by Boss and having the bones installed doesn’t mean you’ll survive being part of the act.

No one joins the Circus Tresaulti who isn’t at least a little bit broken. Valentine’s narrative is equally fractured, slipping from second person to third person, pausing in the present tense and then sliding back into the past. Little George narrates in first person. Elena and a few other characters narrate in third person. The reader also hears whispers and asides from another narrator, the voice of the storyteller, who points out when the characters aren’t quite being honest with themselves. The overall effect is strange, and could be off-putting for many readers. I found it entrancing.

Readers of Fantasy Magazine and Beneath Ceaseless Skies will already be familiar with stories about the Circus Tresaulti. All of those stories are available as podcasts: Study, for Solo Piano; The Finest Spectacle Anywhere; Bread and Circuses. If you’re unsure whether you’ll like Mechanique, give those a listen. The tone and the style of the narration does not change from the stories to the book. Valentine just pulls the curtain back a bit more in her novel, and lets her readers see things that she only hinted at in the short stories.

Mechanique steps away from traditional adult fantasy literature with its illustrations. I heartily approve of this trend. The artist who did the cover (and the promotional Tresaulti tickets) has done a handful of lovely black and white illustrations for the interior. One picture in particular that stands out in my mind is the drawing of Elena sitting alone in the big top, swinging back and forth on the trapeze and staring away into the darkness.

Mechanique is surreal. The narrative is nonlinear and the magic works because Boss says so. Readers looking for traditional fantasy narratives should probably look elsewhere. Fans of Genevieve Valentine, and those readers who are willing to take a risk, should buy a ticket for the Circus Tresaulti. They have beer in glasses, dancing girls, and mechanical marvels to shock and amaze you.