Escape Pod 307: Soulmates

Soulmates

By Mike Resnick and Lezli Robyn

Have you ever killed someone you love – I mean, really love?

I did.

I did it as surely as if I’d fired a bullet into her brain, and the fact that it was perfectly legal, that everyone at the hospital told me I’d done a humane thing by giving them permission to pull the plug, didn’t make me feel any better. I’d lived with Kathy for twenty-six years, been married to her for all but the first ten months. We’d been through a lot together: two miscarriages, a bankruptcy, a trial separation twelve years ago – and then the car crash. They said she’d be a vegetable, that she’d never think or walk or even move again. I let her hang on for almost two months, until the insurance started running out, and then I killed her.

Other people have made that decision and they learn to live with it. I thought I could, too. I’d never been much of a drinker, but I started about four months after she died. Not much at first, then more every day until I’d reach the point, later and later each time, where I couldn’t see her face staring up at me anymore.

I figured it was just a matter of time before I got fired – and you have to be pretty messed up to be fired as a night watchman at Global Enterprises. Hell, I didn’t even know what they made, or at least not everything they made. There were five large connected buildings, and a watchman for each. We’d show up at ten o’clock at night, and leave when the first shift showed up at seven in the morning – one man and maybe sixty robots per building.

Yeah, being sacked was imminent. Problem was, once you’ve been fired from a job like this, there’s nothing left but slow starvation. If you can’t watch sixty pre-programmed robots and make sure the building didn’t blow up, what the hell can you do?

I still remember the night I met Mose.

I let the Spy Eye scan my retina and bone structure, and after it let me in I went directly to the bottle I’d hidden in the back of the washroom. By midnight I’d almost forgotten what Kathy looked like on that last day – I suppose she looked pretty, like she always did, but innocent was the word that came to mind – and I was making my rounds. I knew that Bill Nettles – he was head man on the night shift – had his suspicions about my drinking and would be checking up on me, so I made up my mind to ease off the booze a little. But I had to get rid of Kathy’s face, so I took one more drink, and then next thing I knew I was trying to get up off the floor, but my legs weren’t working.

I reached out for something to steady myself, to lean against as I tried to stand, and what I found was a metal pillar, and a foot away was another one. Finally my eyes started focusing, and I saw that what I had latched onto were the titanium legs of a robot that had walked over when it heard me cursing or singing or whatever the hell I was doing.

“Get me on my feet!” I grated, and two strong metal hands lifted me to my feet.

“All you all right, sir?” asked the robot in a voice that wasn’t quite a mechanical monotone. “Shall I summon help?”

”No!” I half-snapped, half-shouted. “No help!”

“But you seem to be in physical distress.”

“I’ll be fine,” I said. “Just help me to my desk, and stay with me for a few minutes until I sober up.”

“I do not understand the term, sir,” it said.

“Don’t worry about it,” I told him. “Just help me.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Have you got an ID?” I asked as he began walking me to my desk.

“MOZ-512, sir.”

I tried to pronounce it, but I was still too drunk. “I will call you Mose,” I announced at last. “For Old Man Mose.”

“Who was Old Man Mose, sir?” he asked.

“Damned if I know,” I admitted.

We reached the desk, and he helped me into the chair.

“May I return to work, sir?”

“In a minute,” I said. “Just stick around long enough to make sure I don’t have to run to the bathroom to be sick. Then maybe you can go.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“I don’t remember seeing you here before, Mose,” I said, though why I felt the need to make conversation with a machine still eludes me.

“I have been in operation for three years and eighty-seven days, sir.”

“Really? What do you do?”

“I am a troubleshooter, sir.”

I tried to concentrate, but things were still blurry. “What does a troubleshooter do, besides shoot trouble?” I asked.

“If anything breaks on the assembly line, I fix it.”

“So if nothing’s broken, you have nothing to do?”

“That is correct, sir.”

“And is anything broken right now?” I asked.

“No, sir.”

“Then stay and talk to me until my head clears,” I said. “Be Kathy for me, just for a little while.”

“I do not know what Kathy is, sir,” said Mose.

“She’s not anything,” I said. “Not anymore.”

“She?” he repeated. “Was Kathy a person?”

“Once upon a time,” I answered.

“Clearly she needed a better repairman,” said Mose.

“Not all things are capable of repair, Mose,” I said.

“Yes, that is true.”

“And,” I continued, remembering what the doctors had told me, “not all things should be repaired.”

“That is contradictory to my programming, sir,” said Mose.

“I think it’s contradictory to mine, too,” I admitted. “But sometimes the decisions we have to make contradict how we are programmed to react.”

“That does not sound logical, sir. If I act against my programming it would mean that I am malfunctioning. And if it is determined that my programming parameters have been compromised, I will automatically be deactivated,” Mose stated matter-of-factly.

“If only it could be that easy,” I said, looking at the bottle again as a distorted image of Kathy swam before my eyes.

“I do not understand, sir.”

Blinking away dark thoughts, I looked up at the expressionless face of my inquisitor, and wondered: Why do I feel like I have to justify myself to a machine? Aloud I said, “You don’t need to understand, Mose. What you do have to do is walk with me while I start my rounds.” I tried unsuccessfully to stand when a titanium arm suddenly lifted me clear out of the seat, settling me down gently beside the desk.

“Don’t ever do that again!” I snapped, still reeling from the effects of alcohol and the shock at being manhandled, if that term can be applied to a robot, so completely. “When I need help, I’ll ask for it. You will not act until you are given permission.”

“Yes, sir,” Mose replied so promptly I was taken aback.

Well, there’s no problem with your programming, I thought wryly, my embarrassment and alcohol-fueled anger dissipating as I gingerly started out the door and down the corridor.

I approached the first Spy Eye checkpoint on my rounds, allowing it to scan me so I could proceed into the next section of the building. Mose obediently walked beside me, always a step behind as protocol decreed. He had been ordered not to enter Section H, because he wasn’t programmed to repair the heavy machinery there, so he waited patiently until I’d gone through it and returned. The central computer logged the time and location of each scan, which let my supervisor know if I was completing my rounds in a timely fashion – or, as was becoming the case more and more often, if I was doing them at all. So far I’d received two verbal warnings and a written citation regarding my work, and I knew I couldn’t afford another one.

As we made our way through the Assembly Room I begrudgingly had to lean on Mose several times. I even had to stop twice to wait for the room to stop spinning. During that second occasion I watched the robots assigned to this section going about their tasks, and truly looked at them for the first time.

I was trying to put a finger on why their actions seemed…well, peculiar – but I couldn’t tell. All they were doing was assembling parts – nothing strange about that. And then it hit me: It was their silence. None of them interacted with each other except to pass objects – mostly tools – back and forth. There was no conversation, no sound to be heard other than that of machines working. I wondered why I had never noticed it before.

I turned to Mose, whose diligent focus remained on me rather than the other robots. “Don’t you guys ever speak?” I asked, with only a slight slur detectable in my speech. The effect of the alcohol was wearing off.

“I have been speaking to you, sir,” came his measured reply.

Before I could even let out an exasperated sigh or expletive, Mose cocked his head to one side as if considering. I had never seen a robot affect such a human-like mannerism before.

“Or are you are inquiring whether we speak among ourselves?” Mose asked, and waited for me to nod before proceeding. “There is no need, sir. We receive our orders directly from the main computer. We only need to speak when asked a direct question from a Superior.”

“But you have been asking questions of me all night, and even offering opinions,” I pointed out, suddenly realizing that it was Mose’s behavior I found peculiar, not the others who were working on the assembly line. I wasn’t used to robots interacting with me the way Mose had been doing for the past half hour.

I could almost see the cogs working in his head as he considered his reply. “As a troubleshooter I have been programmed with specific subroutines to evaluate, test, and repair a product that is returned to the factory as faulty. These subroutines are always active.”

“So in other words, you’ve been programmed with enough curiosity to spot and fix a variety of problems,” I said. “That explains the questions, but it not your ability to form opinions.”

“They are not opinions, sir,” he said.

“Oh?” I said, annoyed at being contradicted by a machine. “What are they, then?”

“Conclusions,” replied Mose.

My anger evaporated, to be replaced by a wry smile. I would have given him a one-word answer – “Semantics” – but then I’d have had to spend the next half hour explaining it.

We talked about this and that, mostly the factory and its workings, as I made my rounds, and oddly enough I found his company strangely comforting, even though he was just a machine. I didn’t dismiss him when I had successfully completed my first circuit of the building, and he wasn’t called away for any repairs that night.

It was when the first rays of sunlight filtered in through the dust-filmed windows that I realized my time with Mose had been the only companionship I’d shared with anyone (or, in this case,

anything) since Kathy had died. I hadn’t let anyone get close to me since I had killed her, and yet I’d spoken to Mose all night. Okay, he wasn’t the best conversationalist in the world, but I had previously pushed everyone away for fear that they would come to harm in my company, as Kathy had. That was when it hit me: A robot can’t come to harm in my company, because I can’t cause the death of something that isn’t alive in the first place.

On the train home from work, I considered the ramifications of that observation as I reflected on the last thing we’d talked about before dismissing Mose to his workstation. I’d been reaching for my bottle in order to stash it away in its hiding place when he had startled me with another of his disarming opinions.

“That substance impairs your programming, sir. You should refrain from consuming it while you work.”

I had glared at him, an angry denial on the tip of my tongue, when I realized that I was more alert than I had been in months. In fact, it was the first time I’d completed my rounds on schedule in at least a week. And all because I hadn’t had a drop of alcohol since the start of my shift.

The damned robot was right.

I looked at him for a long minute before replying, “My programming was impaired before I started drinking, Mose. I’m damaged goods.”

“Is there anything I can repair to help you function more efficiently, sir?” he inquired.

Startled speechless, I considered my answer – and this time it wasn’t the effects of alcohol that had me tongue-tied. What on earth had prompted such unsolicited consideration from a robot?

I looked closely the robot’s ever-impassive face. It had to be its troubleshooting programming. “Humans aren’t built like machines, Mose,” I explained. “We can’t always fix the parts of us that are faulty.”

“I understand, sir.” Mose replied. “Not all machines can be repaired either. However, parts of a machine that are faulty can be replaced by new parts to fix them. Is that not the same with humans?”

“In some cases,” I replied. “But while we can replace faulty limbs and most organs with artificial ones, we can’t replace a brain when its function is impaired.”

Mose cocked his head to the side again. “Can it not be reprogrammed?”

I paused, considering my answer carefully. “Not in the way you mean it. Sometimes there is nothing left to be programmed again.” A heart-achingly clear image of Kathy laughing at one of my long-forgotten jokes flashed painfully through my mind, followed by a second image of her lying brain-dead on her bed in the hospital.

My fingers automatically twitched for the bottle in front of me, as I forced myself to continue, if only to banish the image of Kathy out of my mind. “Besides, human minds are governed to a great extent by our emotions, and no amount of reprogramming can control how we will react to what we feel.”

“So emotions are aberrations in your programming then?”

I almost did a double take. I’d never looked at it that way before. “Not exactly, Mose. Our emotions might lead us to make mistakes at times, but they’re the key element that allows us to be more than just our programming. I paused, wondering how in hell I was supposed to adequately describe humanity to a machine. “The problem with emotions is that they affect each of our programs differently, so two humans won’t necessarily make the same decision based on the same set of data.”

The sound of a heart monitor flat-lining echoed through the bypasses of my mind. Did I make the right decision, and if so, why did it still torture me day and night? I didn’t want to think about Kathy, yet every one of my answers led to more thoughts of her.

Suddenly, I realized that Mose was speaking again and despite the strong urge to reach forward, grab the bottle and take a mind-numbing swig, I found I was curious to hear what he had to say.

“As a machine I am told what is right and wrong for me to do by humans,” he began. “Yet, as a human your emotions can malfunction even when you do something that is meant to be right. It seems apparent that humans have a fundamental flaw in their construction – but you say that this flaw is what makes you superior to a machine. I do not understand how that can be, sir.”

I’ll tell you, he was one goddamned surprising machine. He could spot a flaw – in a machine or in a statement – quicker than anyone or anything I’d ever encountered. All I could think of was: how the hell am I going to show you you’re wrong, when I don’t know if I believe it myself?

I picked up the bottle, looking at the amber liquid swish hypnotically for a minute before reluctantly stashing it in the back of my desk drawer so I could focus all of my attention on Mose.

“There is something unique about humans that you need to know if you are to understand us,” I said.

“And what is that, sir?” he asked dutifully.

“That our flaws, by which I mean our errors in judgment, are frequently the very things that enable us to improve ourselves. We have the capacity to learn, individually and collectively, from those very errors.” I don’t know why he looked unconvinced, since he was incapable of expression, but it made me seek out an example that he could comprehend. “Look at it this way, Mose. If a robot in the shop makes a mistake, it will continue making the very same mistake until you or a programmer fixes it. But if a man makes the same mistake, he will analyze what he did wrong and correct it” – if he’s motivated and not a total asshole, anyway – “and won’t make the same mistake again, whereas the robot will make it endlessly until an outside agent or agency corrects it.”

If a robot could exhibit emotions, I would have sworn Mose had appeared surprised by my answer. I had expected him to tell me that he didn’t understand a word of what I was saying – I mean, really, what could a machine possibly understand about the intricacies of the human mind? – but once again he managed to surprise me.

“You have given me a lot of data to consider, sir,” said Mose, once again cocking his head to the side. “If my analysis of it is correct, this substance you consume prohibits you from properly evaluating the cause of your problem, or even that you have a problem. So your programming is not impaired as you stated earlier; rather, it is your programming’s immediate environment.”

As I hopped off the train an hour later and trundled off in the direction of my local shopping mall, I could still hear his conclusion reverberating through my mind. I had been so embarrassed by the truth of his statement that I couldn’t even formulate an adequate reply, so I had simply ordered Mose to return to his workstation.

And as I turned and walked down yet another nameless street – they all looked the same to me – I tried to find flaws in what the robot had said, but couldn’t. Still, he was only a machine. How could he possibly understand the way the death of a loved one plays havoc with your mind, especially knowing that you were the one responsible for her death?

Then an almost-forgotten voice inside my head – the one I usually tried to drown out by drinking – asked me: And how does it honor Kathy’s memory to suppress all thoughts of your life together with alcohol? Because if I was to be truly honest with myself, I wasn’t drinking just for the guilt I felt over her death. I did it because I wasn’t ready to think of a future that didn’t include her in it.

Within fifteen minutes I had entered the mall without any recollection of having walked the last few blocks, and automatically started in the direction of the small sandwich shop I frequented. People were making purchases, appearing full of life as they went about their daily routines, but every time a shop window caught my eye I’d peer in and see Kathy as the mannequin, and I’d have to shake my head or blink my eyes very fast to bring back the true picture.

It was only when I reached the shabby out-of-the-way corner of the mall that contained the liquor store, a rundown news agency that I never entered, and the grubby little sandwich shop that supplied my every meal, that I began to relax. This was the only place where I wasn’t haunted by my memories. Kathy would never have eaten here, but the little shop with its peeling paint and cheap greasy food was a haven for me because of the dark secluded corner table where the proprietor would allow me to consume my alcohol in privacy – as long as I continued to buy my food from him.

I ordered the usual, and ate my first meal since the previous night while I considered the ramifications of what Mose had said. Then, suddenly, I was being prodded awake by the owner. Not that being nudged or even shaken awake was strange in itself, but usually I passed out, dead drunk, in the booth; I didn’t simply fall asleep.

I looked at my watch realized I had to go home to prepare for my next shift or risk losing my job. Then it dawned on me: I hadn’t consumed a single drop of alcohol since I’d met Mose the previous night. Even more startling was the realization that I was actually looking forward to going to work, and I knew instinctively that Mose was the cause of it, him and his attempts to diagnose how to “repair” me. When all was said and done, he was the only entity other than Kathy who had ever challenged me to improve myself.

So when I entered the building two hours later and began making my rounds, I kept an eye out for Mose. When it became clear that he was nowhere to be found on the assembly floor, I sought out his workstation, and found him in what looked like a Robot’s House of Horrors.

There were metallic body parts hanging from every available section of the ceiling, while tools – most of them with sharp edges, though there was also an ominous-looking compactor – lined all of the narrow walls. Every inch of his desk was covered with mechanical parts that belonged to the machines on the factory floor, or the robots that ran them. As I approached him, I could see diagnostic computers and instruments very neatly lining the side of his workstation.

“Good evening, sir,” said Mose, looking up from a complicated piece of circuitry he was repairing.

I just stared at him in surprise, because I had been expecting the usual greeting of “How may I help you, sir?” which I had heard from every factory robot I had ever approached. Then I realized that Mose had taken me at my word when I’d ordered him not to help me unless I’d asked for it. Now he wasn’t even offering help. He was one interesting machine.

“You are damaged again, sir,” he stated in his usual forward manner. Before I could gather my wits about me to reply, he continued: “Where you used to have a multitude of protrusions on your face, you now have random incisions.”

I blinked in confusion, automatically raising my hand to rub my face, wincing when my fingers touched sections of my jaw where the razor had nicked my skin. He was talking about my beard – or lack of one now. I still couldn’t believe I had let one grow for so long. Kathy would have hated it.

“The damage is minimal, Mose,” I assured him. “I haven’t shaved – the process by which a human gets rid of unwanted facial hair – in a long time, and I’m a little out of practice.”

“Can humans unlearn the skills they acquire?” Mose inquired, with that now familiar tilt of the head.

“You’d be surprised at what humans can do,” I said. “I certainly am.”

“I do not understand, sir,” he said. “You are inherently aware of your programming, so how can a human be surprised at anything another human can do?”

“It’s the nature of the beast,” I explained. “You are born – well, created – fully programmed. We aren’t. That means that we can exceed expectations, but we can also fall short of them.”

He was silent for a very long moment, and then another.

“Are you all right, Mose?” I finally asked.

“I am functioning within the parameters of my programming,” he answered in an automatic fashion. Then he paused, putting his instruments down, and looked directly at me. “No, sir, I am not all right.”

“What’s the matter?”

“It is inherent in every robot’s programming that we must obey humans, and indeed we consider them our superiors in every way. But now you are telling me that my programming may be flawed precisely because human beings are flawed. This would be analogous to your learning from an unimpeachable authority that your god, as he has been described to me, can randomly malfunction and can draw false conclusions when presented with a set of facts.”

“Yeah, I can see where that would depress you,” I said.

“It leads to a question which should never occur to me,” continued Mose.

“What is it?”

“It is…uncomfortable for me to voice it, sir.”

“Try,” I said.

I could almost see him gathering himself for the effort.

“Is it possible,” he asked, “that we are better designed than you?”

“No, Mose,” I said. “It is not.”

“But—”

“Physically some of you are better designed, I’ll grant you that,” I said. “You can withstand extremes of heat and cold, your bodies are hardened to the point where a blow that would cripple or kill a man does them no harm, you can be designed to run faster, lift greater weights, see in the dark, perform the most delicate functions. But there is one thing you cannot do, and that is overcome your programming. You are created with a built-in limitation that we do not possess.”

“Thank you, sir,” said Mose, picking up his instruments and once again working on the damaged circuitry in front of him.

“For what?” I asked.

“I take great comfort in that. There must be a minor flaw in me that I cannot detect, to have misinterpreted the facts and reached such an erroneous conclusion, but I am glad to know that my basic programming was correct, that you are indeed superior to me.”

“Really?” I said, surprised. “It wouldn’t please me to know that you were superior.”

“Would it please you to know your god is flawed?”

“By definition He can’t be.”

“By my definition, you can’t be,” said Mose.

No wonder you’re relieved, I thought. I wonder if any robot has ever had blasphemous thoughts before?

“Because if you were,” he continued, “then I would not have to obey every order given me by a human.”

Which got me to thinking: Would I still worship a God who couldn’t remember my name or spent His spare time doing drugs?

And then came the kind of uncomfortable thought Mose had: how about a God who flooded the Earth for forty days and nights in a fit of temper, and had a little sadistic fun with Job?

I shook my head vigorously. I decided that I found such thoughts as uncomfortable as Mose did.

“I think it’s time to change the subject,” I told him. “If you were a man, I’d call you a soulmate and buy you a beer.” I smiled. “I can’t very well buy you a can of motor oil, can I?”

He stared at me for a good ten seconds. “That is a joke, is it not, sir?”

“It sure as hell is,” I said, “and you are the first robot ever to even acknowledge that jokes exist, let alone identify one. I think we are going to become very good friends, Mose.”

“Is it permitted?” he asked.

I looked around the section. “You see any man here besides me?”

“No, sir.”

“Then if I say we’re going to be friends, it’s permitted.”

“It will be interesting, sir,” he finally replied.

“Friends don’t call each other ‘sir’,” I said. “My name is Gary.”

He stared at my ID tag. “Your name is Gareth,” he said.

“I prefer Gary, and you’re my friend.”

“Then I will call you Gary, sir.”

“Try that again,” I said.

“Then I will call you Gary.”

“Put it there,” I said, extending my hand. “But don’t squeeze too hard.”

He stared at my hand. “Put what there, Gary?”

“Never mind,” I said. And more to myself than him: “Rome wasn’t built in a day.”

“Is Rome a robot, Gary?”

“No, it’s a city on the other side of the world.”

“I do not think any city can be built in a day, Gary.”

“I guess not,” I said wryly. “It’s just an expression. It means some things take longer than others.”

“I see, Gary.”

“Mose, you don’t have to call me Gary every time you utter a sentence,” I said.

“I thought you preferred it to sir, Gary.” Then he froze for a few seconds. “I mean to sir, sir.”

“I do,” I said. “But when there’s only you and me talking together, you don’t have to say Gary every time. I know who you’re addressing.”

“I see,” he said. No “Gary” this time.

“Well,” I said, “now that we’re friends, what shall we talk about?”

“You used a term I did not understand,” said Mose. “Perhaps you can explain it to me, since it indirectly concerned me, or would have had I been a human.”

I frowned. “I haven’t the slightest idea what you’re talking about, Mose.”

“The term was soulmate.”

“Ah,” I said.

He waited patiently for a moment, then said, “What is a soulmate, Gary?”

“Kathy was a soulmate,” I replied. “A perfect soulmate.”

“I thought you said that Kathy malfunctioned,” said Mose.

“She did.”

“And malfunctioning made her a soulmate?”

I shook my head. “Knowing her, loving her, trusting her, these things made her my soulmate.”

“So if I were a man and not a robot, you would know and love and trust me too, Gary?” he asked.

I couldn’t repress a smile. “I know and like and trust you. That is why you are my friend.” I was silent for a moment, as images of Kathy flashed through my mind. “And I’d never do to you what I did to her.”

“You would never love me?” said Mose, who had no idea what I had done to her. “The word is in my databank, but I do not understand it.”

“Good,” I told him. “Then you can’t be hurt as badly. Losing a friend isn’t like losing a soulmate. You don’t become as close.”

“I thought she was terminated, not misplaced, Gary.”

“She was,” I said. “I killed her.” I stared into space. The last six months faded away and I remember sitting by Kathy’s hospital bed again, holding her lifeless hand in mine. “They said there was no hope for her, that she’d never wake up again, that if she did she’d always be a vegetable. They said she’d stay in that bed the rest of her life, and be fed with tubes. And maybe they were right, and maybe no one would ever come up with a cure for her. But I didn’t wait to find out. I killed her.”

“If she was non-functional, then you applied the proper procedure,” said Mose. He wasn’t trying to comfort me; that was beyond him. He was just stating a fact as he understood it.

“I loved her, I was supposed to protect her, but I was the one who crashed the car, and I was the one who pulled the plug,” I said. “You still want to know why I drink?”

“Because you are thirsty, Gary.”

“Because I killed my soulmate,” I said bitterly. “Maybe she’d never wake up, maybe she’d never know my name again, but she’d still be there, still be breathing in and out, still with a one-in-a-million chance, and I put an end to it. I promised to stay with her in sickness and in health, and I broke that promise.” I started pacing nervously around his work station. “I’m sorry, Mose. I don’t want to burden you with my problems.”

“It is not a burden,” he replied.

I stared at him for a moment. Well, why should you give a shit?

“Wanna talk baseball?” I said at last.

“I know nothing about baseball, Gary.”

I smiled. “I was just changing the subject, Mose.”

“I can tie in to the main computer and be prepared to talk about baseball in less than ninety seconds, Gary,” offered Mose.

“It’s not necessary. We must have something in common we can talk about.”

“We have termination,” said Mose.

“We do?”

“I terminate an average of one robot every twenty days, and you terminated Kathy. We have that in common.”

“It’s not the same thing,” I said.

“In what way is it different, Gary?” he asked.

“The robots you terminate have no more sense of self-preservation than you have.”

“Did Kathy have a sense of self-preservation?” asked Mose.

You are one smart machine, I thought.

“No, Mose. Not after the accident. But I had an emotional attachment to her. Surely you don’t have one to the robots you terminate.”

“I don’t know.”

“What do you mean, you don’t know?” I said irritably. I was suddenly longing for a drink, if only to drown out all the painful memories of Kathy that I’d conjured up.

“I don’t know what an emotion is, Gary,” answered Mose.

“You don’t know what a lucky sonuvabitch you are,” I said bitterly.

“Yes, I do,” he said, once again surprising me out of my dark thoughts.

“You are a never-ending source of wonder to me, Mose,” I replied. “You want to explain that remark?”

“You are my friend. No other robot has a friend. Therefore, I must be a lucky sonuvabitch.”

I laughed and threw my arm around his hard metal body, slapping his shoulder soundly in a comradely fashion.

“You are the only thing that’s made me laugh in the last six months,” I said. “Don’t ever change.”

If a robot could noticeably stiffen or project confusion, then that was his reaction. “Is it customary for friends to hit each other, Gary?”

It took me a good five minutes to explain my actions to Mose. At first I was surprised that I even bothered. Hell, between my drinking and my bitterness over Kathy’s death I’d already alienated my entire family, and to tell the truth I didn’t care what any of them thought of me – but that damned machine had a way of making me take a good, hard, honest look at myself whenever he asked one of his disarming questions, and I suddenly realized that I didn’t want to disappoint him with my answers. More to the point, I was tired of disappointing me. If I was his notion of humanity, maybe I owed both of us a better effort.

By the time I returned home at the end of my shift I was bone-weary, but I couldn’t sleep because I had a splitting headache. I was also surprised to discover that I was incredibly hungry, which was unusual for that time of day. And then, as I groped around the dusty medicine cabinet for some painkillers, I realized why: it had been nearly two days since my last drink. It was no wonder I was hungry – I was withdrawing from alcohol abuse and my body was craving substance.

I went into the kitchen to pour out a drink to down the pills, but I realized that the fridge only held beer, the countertop was scattered with half-empty bottles of spirits, and the sink was full of discarded bottles. There wasn’t a single non-alcoholic beverage in the entire apartment.

I wasn’t suicidal or stupid enough to mix alcohol with medicine, so I downed the tablets with a glass of water. (Well, a cupped handful of water. I hadn’t washed a glass in months.)

I left the kitchen, firmly closing the door behind me, and took a hot, soothing shower. It helped calm the shakes, and when the pills started to take effect and I could think more clearly, I grinned at the irony of my situation. I had come straight home without going to the mall to try and break the cycle of drinking, only to discover that my house was even more of alcoholic trap.

I lay down and was soon asleep, but like always I kept reliving the car crash in my dreams. I woke up dripping with sweat and started pacing the room. If only my reflexes hadn’t been slowed by alcohol, I would have reacted quicker when the other car had run the red light. It didn’t matter that the blood test revealed I’d been under the legal limit and the skid marks showed the other guy was at fault. The simple fact was that if I’d been sober, Kathy would still be alive.

I left the bedroom and turned on the television to distract myself from those thoughts. I looked around the room. I hadn’t cleaned it in months, and dust covered every surface. I waited for the loneliness to set in – even turning the photos to the wall hadn’t helped – and suddenly realized that there was something in my life that finally did interest me: Mose, with his unsolicited opinions and his engaging wish to learn more about humanity.

I changed the channel and settled down to watch a basketball game – and promptly fell asleep. By the time I woke up, the game had long finished – not that basketball interested me much anymore – and I discovered that I had slept most of the day away. Strangely enough, instead of being disappointed at a day lost, I found that I looked forward to my next conversation with Mose.

So I turned up early for my next shift at the factory. I was placing the sandwich I’d bought at a corner store in my desk drawer, careful not to touch the half-empty flask lying beside it, when a shadow fell over my desk. I slammed the drawer shut, expecting Bill Nettles to be standing in the doorway, but it was Mose. I was pleasantly surprised: it was the first time he had sought me out.

“Your watch must be malfunctioning,” he stated, not missing a beat. “Your shift is not due to start for seventeen minutes, Gary.”

“My watch is not malfunctioning,” I said. “I’m just functioning more efficiently tonight.”

“It is efficient to arrive for your shift at the wrong time?” he inquired in a voice that I could swear modulated more than it used to. I could almost hear his curiosity now.

“No, Mose, but it is efficient to arrive early – if you can understand the distinction.” I paused. “Never mind that. Why were you coming to my office before I started work anyway?”

“To wait for you.”

It was like pulling teeth. “Why did you want to wait for me?”

“I need your input concerning the termination of another robot.”

My eyebrows furrowed in confusion. “Did another human order its deactivation?”

“Yes, Gary.”

“Then why haven’t you simply obeyed the command? I don’t have the mechanical expertise to diagnose the status of a malfunctioning robot. I assume the other human does.”

His head cocked to the side, as if considering his answer. I realized it was a trait he’d picked up from me. “I do not need input on the mechanical status of the robot.. I believe his condition does not necessitate termination, and I would like to evaluate your opinion.”

I couldn’t hide my surprise. “You’re asking me for advice?”

“Is this not the function of a friend – to give advice?”

“Yes, it is,” I replied, “but I’m no expert on robots.”

“You have terminated another being. We will compare data to determine if this robot should also be terminated.”

“The circumstances are vastly different, Mose,” I told him.

“You said that if you did not terminate Kathy there was a possibility that she could have regained all of her functions,” noted Mose.

“I said there was an outside possibility that she might have,” I explained. “She was diagnosed as brain-dead. All of her programming was destroyed, Mose. To merely exist is not living. Even if the day came that she no longer needed the life support, the Kathy I knew was gone forever.”

“I understand,” he replied. “However, this robot’s programming is intact.”

I look up at him in surprise. “You’ve communicated with it?”

“Yes, Gary,” he replied. “In order to ascertain the condition of its programming.”

He asked the robot how it felt? That was such a human thing to do. “Were you told to repair the robot?” I finally asked.

“No.”

“Then why haven’t you simply terminated it as you were ordered to?”

“Would you have terminated Kathy if she had have been able to communicate with you?”

“Of course not,” I replied. “But terminating a robot is very different from killing a human. It’s just a machine.” And suddenly I felt guilty for saying that to another machine. “Did this robot tell you that it doesn’t want to be terminated?”

“No, Gary. Indeed, it says that it no longer has any functions to perform and therefore has no logical purpose to exist.”

“Well then, I don’t understand the problem.” I said, feeling more at ease. “Even the robot agrees that it should be terminated.”

“Yes,” agreed Mose, “but only because it has been ordered to comply, Gary.”

“No,” I said. “It’s because this robot has no sense of self-preservation. Otherwise it would object to termination regardless of its orders.”

He considered me for a long minute before replying. “So you are telling me that because robots do not have self-preservation it is acceptable to terminate them without any other reason or justification.” It was worded as a statement, but it felt like a question. “You also stated yesterday that Kathy no longer had self-preservation.”

The impact of Mose’s observation was unavoidable. I sat down at my desk, my mind going back to that fateful day six months ago when the doctors had told me that it was unlikely that Kathy would recover. Once I knew she was brain-dead and couldn’t decide her own fate, did that make it not just acceptable but easier for me to decide to terminate her life-support? Did knowing that she could no longer fight for life justify killing her?

I agonized over those dark thoughts for some time before I concluded that no, that was definitely not why I had told them to pull the plug. It was cruel to keep her alive with machines when everything that made her Kathy was gone. Which led to another uncomfortable question: cruel to her, or cruel to me?

It was only when Mose spoke up again that I realized that I must have voiced my thoughts out loud.

“Did you make the correct decision?” he asked.

“Yes, I did,” I said, and added silently: at least I hope so. “But it will always feel wrong to a human to take the life of someone he loves, regardless of the justification.”

Mose began walking around the room. Was he pacing? I often did that when distressed. It must have been something else he’d picked up from me.

Suddenly he stopped and turned to me. “I am not capable of love, but I believe it is wrong to terminate this robot’s existence.”

“Why?” I asked him.

“It is possible to repair him.”

I stared at him in surprise. What I didn’t ask then – what I should have asked – was why Mose felt compelled to fix the robot. Instead I said, “Do you realize that you yourself could be deactivated if you disobey your superiors?”

“Yes,” he answered matter-of-factly.

“Doesn’t that bother you?” It sure as hell bothered me.

“I have no sense of self-preservation either, Gary.”

I realized the damned robot was throwing my own reasoning back in my face. “How does it make sense for you to repair a robot that no longer performs a function for the company, knowing that it will probably result in the termination of a perfectly-functioning robot – yourself?”

“If I were damaged, would you terminate me, knowing that I could be repaired?” he asked calmly.

No, I would not, Mose.

But I couldn’t tell him that, because that would validate his argument, and I could lose what had become my only friend. “Where in the hell did you pick up such an annoying habit of answering a question with a question?” I asked instead. Then I realized what I had done and laughed. “Never mind.”

We shared a moment of awkward silence – at least, on my side it was awkward – while I considered everything he had told me, trying to find the best solution to his dilemma. Which led to a very logical thought: why terminate any robot if it could be repaired, given new orders, and transferred or sold elsewhere? Robots were expensive.

“You said that you could repair the robot,” I stated more than asked.

“Yes.”

“Can you tell me what’s wrong with this robot?”

“It requires new parts to replace its upper limbs and most of its torso. However, I do not have the prerequisite parts in my workshop as this model is from a discontinued line.”

Now I was beginning to understand. “So, as troubleshooter, you tied in to the main computer, saw that the parts were available elsewhere, requested them, and were denied?”

“That is correct. I was told that repairing the robot was not feasible for the company.”

“Okay, now I know what’s going on,” I told him. And I knew how I could logically convince him that repairing this robot was not worth ending his existence. “And I know why you are not allowed to fix it. The creation of a robot is very complex and expensive, so every robot that’s bought by the company is a long-term investment. But once a particular model has been discontinued, spare parts are no longer manufactured for it – so it’s often more expensive to buy these limited replacement parts than it is to purchase a completely new and more advanced robot right off the assembly line. Do you follow me, Mose?”

“Yes, Gary,” he replied. “Their decision is based on what is cost effective for the company.”

“Exactly,” I replied, glad he grasped it so easily. “So this robot will be replaced by a model that is more valuable to the company and you don’t have to waste your time repairing it.”

“If Kathy could have been fixed,” he asked suddenly, “would you have decided that it was more cost effective to select a new soulmate, rather than spend the time and effort to repair her?”

I sighed in frustration: this was going to be harder than I thought. “No, I would not, Mose – but you can’t compare a robot’s value to Kathy’s. She was unique. This robot is only a machine, one of many just like it that have come off an assembly line.”

“This robot is a model DAN564, Gary. There were only eight hundred manufactured in the world. Kathy was a woman and there are more than five billion of them. Can you please explain how this makes her existence more valuable than the robot’s?”

I grimaced. How could Mose always have such a logical rebuttal to all of my responses, and at the same time be so wrong?

“Like I told you, Kathy was my soulmate. There may be five billion women, but she was like no other.” I paused, trying to figure out how I could make him understand. “Remember when I told you that humans are not born fully-programmed like robots, and that our emotions can result in us reacting differently to the same set of data? Well, the process by which we learn and develop our programming is what makes each of us different from all the others. That’s why a human life is more valuable than a robot’s. When one of us dies, we can’t be replaced.”

For once it appeared Mose was at a loss for words. It took him a moment to respond. “You said that Kathy was unique to you because she was your soulmate,” he stated finally.

I agreed, curious as to where this was heading.

“Well, I am a lucky sonuvabitch because I am the only robot to have a friend.” He paused, significantly. “Does that make me unique among all other robots with my model number?”

“Yes, Mose,” I told him, “it definitely does.” I looked at him for a long moment, realizing that not only did I enjoy his company, but I was actually growing quite fond of him. “And that is why you shouldn’t repair this other robot, if the cost is your termination. Where would I find another friend exactly like you?”

He was silent again for another moment. “I will not repair it,” he said at last.

And that was the beginning of a new phase of our relationship, if one can be said to have a relationship with a machine. Every night he’d be waiting for me, and every night, unless he was doing an emergency fix on some circuitry, he’d walk along with me as I made my rounds, and we’d talk. We talked about anything that came into my head. I even began teaching him about baseball. I brought him the occasional newsdisk to read, and I’d answer endless questions about what the world was like beyond the confines of the factory.

And every night he would question me again about the morality of his action, about not repairing the robot when he had the opportunity to.

“It still seems wrong, Gary,” he said one evening, as we discussed it yet again. “I understand that it would not have been cost effective to repair it, but it seems unfair that it should be terminated for reasons of economics.”

“Unfair to whom?” I asked.

He stared at me. “To the robot.”

“But the robot had no sense of self-preservation,” I pointed out. “It didn’t care.” I stared back at him. “Now why don’t you tell me the real reason?”

He considered the question for a minute before answering. “I care,” Mose stated finally.

“You’re not supposed to, you know,” I said.

“Talking with you has increased my perceptions,” he said. “Not my mechanical perceptions; they are pre-programmed. But my moral perceptions.”

“Can a robot have moral perceptions?” I asked.

“I would have said no before I met you, Gary,” said Mose. “And I think most robots cannot. But as a troubleshooter, I am not totally pre-programmed, because I must adjust to all conceivable situations, which means I have the capacity to consider solutions that have never been previously considered to problems that have never previously arisen.”

“But this wasn’t a problem that you’d never faced before,” I pointed out. “You once told me that you deactivated a robot every three weeks or so.”

“That was before I met a man who still suffered from guilt six months after deactivating a soulmate.”

“You know something, Mose?” I said. “I think you’d better not discuss this with anyone else.”

“Why?” he asked.

“This is so far beyond your original programming that it might scare them enough to re-program you.”

“I would not like that,” said Mose.

Likes and dislikes from a robot, and it sounded normal. It would have surprised me, even shocked me, two months earlier. Now it sounded reasonable. If fact, it sounded exactly like my friend Mose.

“Then just be a substitute soulmate to me, and be a robot to everyone else,” I said.

“Yes, Gary, I will do that.”

“Remember,” I said, “never show them what you’ve become, what you are.”

“I won’t, Gary,” he promised.

And he kept that promise for seven weeks.

Then came the day of The Accident. Mose was waiting for me, as usual. We talked about the White Sox and the Yankees, about (don’t ask me why) the islands of the Caribbean, about the 18th and 21st Amendments to the Constitution (which made no sense to him – or to me either) – and, of course, about not salvaging the other robot.

As we talked I made my rounds, and we came to a spot where we had to part company for a few minutes because I had been given extra orders to inspect Section H where Mose was not permitted to go; he was not programmed to repair the heavy machinery that resided there.

As I began walking through Section H, there was a sudden power outage, all the huge machines came to a sudden stop, and the lights went out. I waited a couple of minutes, then decided to go back to my desk and report it, in case it hadn’t extended to the other night watchmen’s domains.

I started feeling my way back between the machines when the power suddenly came on. The powerful lights shone directly in my eyes, and, blinded, I stumbled to my left – and tripped against a piece of heavy machinery that began flattening and grinding something on its rough surface. It wasn’t until I heard a scream and thought it sounded familiar that I realized that what it was flattening and grinding was me.

I tried to pull free, and nothing happened except that it began drawing me farther into the machine. I felt something crushing my legs, and I screamed again – and then, as if in a dream, I seemed to see Mose next to me, holding up part of the machine with one powerful hand, trying to pull me out with another.

“Stop! Don’t get yourself killed too!” I rasped. “I can’t be saved!”

He kept trying to ease me out of the machine’s maw.

The very last words I heard before I passed out, spoken in a voice that was far too calm for the surroundings, were “You are not Kathy.”

I was in the hospital for a month. When they released me I had two prosthetic legs, a titanium left arm, six healing ribs, severance pay, and a pension.

One company exec looked in on me – once. I asked what had become of Mose. He told me that they were still pondering his fate. On the one hand, he was a hero for saving me; on the other, he had seriously damaged a multi-million-dollar machine and disobeyed his programming.

When I finally got home and made my way gingerly around the house on my new legs, I saw what my life had degenerated into following Kathy’s death. I opened all the doors and windows in an attempt to clear out the stale air and started clearing away all the rubbish. Finally I came to a half-empty bottle of whisky. I picked it up with my titanium hand and paused, struck by the irony of the image.

I had a feeling that every time I looked at my new appendage I’d be reminded of my mostly-titanium friend and all he had done for me. And it was with that hand that I poured the contents down the sink.

I spent two weeks just getting used to the new me – not just the one with all the prosthetic limbs, but the one who no longer drank. Then one day I opened the door to go to the store and found Mose standing there.

“How long have you been here?” I asked, surprised.

“Two hours, thirteen minutes, and—”

“Why the hell didn’t you knock?”

“Is that the custom?” he asked, and it occurred to me that this would be the very first non-automated doorway he’d ever walked through.

“Come in,” I said, ushering him into the living room. “Thank you for saving me. Going into Section H was clearly against your orders.”

He cocked his head to one side. “Would you have disobeyed orders if you knew your soulmate could have been saved?”

Yes.

“Your eye is leaking, Gary,” Mose noted.

“Never mind that,” I replied. “Why are you here? Surely the company didn’t send you to welcome me home.”

“No, Gary. I am disobeying standard orders by leaving the factory grounds.”

“How?” I asked, startled.

“As a result of the damage I sustained to my arm and hand” – he held up the battered, misshapen limb for me to see – “I can no longer complete delicate repair work. A replacement part was deemed too expensive, so I was transferred out of the troubleshooting department to basic assembly, where the tasks are menial and repetitive. They will reprogram me shortly.” He paused. “I have worked there continuously until the main computer confirmed today that your employment had been officially terminated. I felt compelled to find out if that termination was a result of your death. I will not remember you or the incident once I am reprogrammed, so I felt it was imperative to find out if I had indeed saved my friend before I no longer care.”

I stared at him silently for a long moment, this supposedly soulless machine that had twice overcome its programming on my behalf. It was all I could do not to throw my arms around his metal body and give him a bear hug.

“They can’t reprogram you if you don’t go back, Mose,” I said at last. “Just wait here a minute.”

I made my way to the bedroom and threw some clothes into a knapsack, pausing only to pick up a framed photo of Kathy to stash in the bag. Then I walked back to the living room.

“Mose,” I said, “how would you like me to show you all the places we talked about over the months?”

He cocked his head to the side again, a gesture I recognized fondly. “I would…enjoy…that, Gary.”

A minute later we were out the door, heading to the bank to withdraw my savings. I knew they’d be looking for him, either because he was so valuable or because he was the only robot ever to overcome his programming, so I wouldn’t be cashing pension checks and letting them know where we were. I instructed him that if anyone asked, he was to say that he was my personal servant. Then we headed to the train station.

And that’s where things stand now. We’re either sightseeing or on the lam, depending on your point of view. But we’re free, and we’re going to stay that way.

I was responsible for one soulmate’s death. I’m not going to be responsible for another’s.

About the Authors

Lezli Robyn

Lezli Robyn loves writing sf, fantasy, horror, humour and even dabbles in steampunk every now and then. She has made over 25 story sales to professional markets around the world, including Asimov’s, Analog and Clarkesworld, and her first short story collection, BITTERSUITE, will be published by TICONDEROGA PRESS in September 2013. She was a finalist for the 2009 Australian AUREALIS AWARD for Best SF Story, the 2010 Spanish IGNOTUS AWARD for Best Foreign Short Story, and was a 2010 CAMPBELL AWARD NOMINEE for best new writer. In 2011 she won the Catalan Best Foreign Translation ICTINEUS AWARD for “Soulmates”, a novelette written with Mike Resnick, which was first published in Asimov’s. Lezli and Mike will be collaborating again soon on an as yet untitled Stellar Guild book together, to be published in 2014.

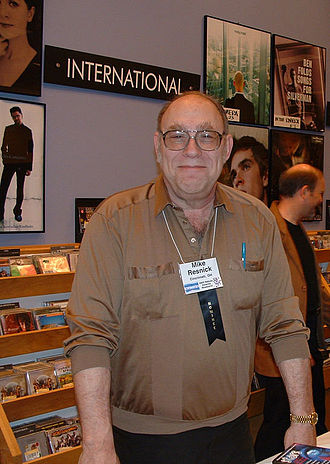

Mike Resnick

Mike Resnick is an American science fiction writer and was executive editor of Jim Baen’s Universe. Resnick’s style is known for the inclusion of humor; he has probably sold more humorous stories than any science fiction author except Robert Sheckley, and even his most grim and serious stories have frequent unexpected bursts of humor in them. Resnick enjoys collaborating, especially on short stories.

About the Narrator

Dave Thompson

Dave Thompson aka the Easter Werewolf aka the California King is still uncomfortable with the notion of pumpkin beer, but don’t hold that against him. He lives outside Los Angeles with his wife and three children. Together with co-editor Anna Schwind, he ran PodCastle for five years, stepping down to focus on his own writing in 2015. You can find two of his audiobook narrations on Amazon: Norse Code by Greg Van Eekhout and Briarpatch by Tim Pratt. Dave is an Escape Artists’ Worldwalker and Storyteller, having been published in, and narrated for, all four EA podcasts.