Escape Pod 583: The Librarian

The Librarian

by Andrew Kozma

People call Matt a librarian, but he doesn’t mind. He takes care of the books, so the name makes sense, even if most of that care involves cleaning up their shit and piss, and feeding them nutritious glop in those moments between hits. If he can convince them to eat. If they aren’t so taken over by ledge they don’t move for months at a time, muscles withering like grapes on the vine.

Matt feels more like a drug dealer, even though he is, at best, an enabler. The libraries spit out blue wedges of ledge for anyone to pick up. He’s tried to get rid of the the libraries before, herding them away from the centers of human population, but no matter how far he drove them, a few days later they’d return to where they’d been, their stubby little crab legs clicking on the concrete. And because the libraries follow demand, the streets outside Heyman’s are littered with the little fuckers. He’s just thankful they don’t come inside—some latent biological programming keeps them from entering buildings.

Matt stores the books in what used to be Heyman’s Department Store, a four-story monstrosity which probably took up an entire city-block on Earth, in whatever city it was taken from, but here it’s lost among randomly scattered skyscrapers, row houses, suburban nuclear-family homes, churches, clubs, and sports arenas. He thinks of it as a temple. Or a museum. He tries not to think of it as a tomb. Most of the time, he’s the only non-ledged human there.

And most of the time, when he’s not cleaning up after or feeding the books, Matt sits at a desk at the entrance of Heyman’s. He reads the Daily Record, a thin newspaper that carries only the barest of actual news, but is stuffed with tons of useless gossip. There’s a crossword inside that uses words taken from the alien races in the surrounding ghettoes, and though that’s the only reason he subscribes to the Record, he reads the whole paper before doing the puzzle just to prolong the pleasure.

“How the day goes?” a lamppost asks. The alien’s glowing head is featureless and too bright to look at directly, but Matt knows it has to be Joking, the only one of its kind to be here every single day, showing up like clockwork at ten am.

“The day goes jokingly.”

The lamppost bobs its head in laughter, strobing the room in shadows. Matt isn’t sure Joking understands what it’s laughing at, but the lamppost has studied human ways well enough it can tell when it’s supposed to laugh. Since Matt’s isolated from his own kind for the most part, he appreciates the veneer of comradery, however false the reality.

Matt records Joking’s name and the alien presses down its signature with a crystalline arm-stalk and the lamppost slides into the main section of the library, hundreds of tiny feet tapping in a continuous stream of sound.

Out through the front windows, behind the array of hopeful libraries, the traffic is constant. Humans make up most of the passersby, but there are enough aliens to make it interesting. Who knows where they’re going or what they want? Most of them aren’t coming to bother him, and Matt’s fine with that. Heyman’s is a destination point of scholars and lawyers, of doctors and scientists, those who want to hunt down and compare the finest points of galactic history.

The libraries exist everywhere in the Inside-Out so any being who wants can take ledge. It’s a service of the Topoi, and they believe (if they can be said to believe—no one understands them even to the littlest degree, though some charlatan jerks pretend to) that service should be free. Humans receive ledge cakes, while others inject it, and still others breathe it. But humanity is gifted or cursed with an affinity for ledge that far outdistances any other race on the Inside-Out. Instead of accessing the Central Galactic Archive, a human taking ledge essentially becomes part of it. They plug themselves in, and literally lose their minds and their very selves to the incomprehensible amounts of information stored in the CGA. And since the other races have discovered this little quirk of human biology, humanity finally has something to offer greater galactic society.

Matt’s attention is speared by a group of teenagers gathered near the libraries outside. A tall boy with hair shaven into patchy spikes runs his fingers over the mouth of a library. Obediently, it spits out a hunk of ledge.

Matt shoves back his chair and runs to the front door, whipping it open so fast it slams into the wall, deepening the gouge already there.

“What the fuck are you all doing?” he asks, his voice a smear of anger. “You know what that stuff is?”

The boy holding the ledge nearly drops it under Matt’s withering stare, but a girl next to him takes the ledge and mimes nibbling it. Her hair is tied off into six pigtails, mimicking the look of a squid’s tentacle brain. Each member of the small group has some sort of affectation like that. Another girl sports metal plates over her skin. A boy with cheap bio-mechanical arms attached to his jacket shuffles his feet.

“Look, old-timer,” the girl sneers. “We know what this is. It’s our ticket out of this place. And just because you’re too afraid to use it, doesn’t mean we are. We’re not afraid of nothing, pchanga.”

Matt’s barely thirty. These kids are fifteen at most. The girl pronounces the alien curse word as though she was born speaking the language.

To prove her point, the girl takes a big bite of the ledge, right as Matt says, “Don’t,” because he can’t not try to stop her. She looks straight at him, chewing deliberately, so he’s the only one there who sees the fear in her eyes, the unsureness, and that tiny moment of shock as she begins to dissolve into the CGA. A second later, she’s a statue, her consciousness on hiatus, no more the girl she was before that bite of ledge than the sidewalk her body stands on.

The rest of the kids look at her in horrified fascination. They’ve seen books before. You can’t avoid them on the streets or clogging up the parks where the kind-hearted relocate them. But they’ve never seen it up this close, the change, how the person you know absents herself from the world.

“Crane?” The tall boy taps his friend’s shoulder. “Are you okay?”

“Please restate the question,” the book says. Even the girl’s voice is gone, modified by the CGA to be something flat and mechanical, more sickening because the ghost of the girl’s non-ledge voice is still there.

A few of the kids slip away. Then the rest, all of them except the tall boy, and him so engrossed in what happened to his friend he doesn’t even notice at first. The girl with the metal plates, she clanks as she walks which finally draws his attention.

“It’s her yannow, hume,” the girl says, still backing away. “Not mine. Not yours.”

The tall boy opens his mouth, but the girl’s turned away now and he’s staring at the backs of his retreating friends. He faces Matt. “How long?”

“A few days. A month. It’s impossible to know.”

“Fuck you, Crane,” he says, voice more sad than angry. He picks her up and walks in the direction of the other kids, but he only gets her a few steps before he loses his hold and she drops to the ground. The boy only barely keeps her from toppling over and slamming face-first into the ground.

“Be careful,” Matt calls out.

“I am!”

“A lot of books break bones like that.”

The boy glares so fiercely Matt’s convinced he’d charge across the short distance between them and beat his face in, if he wasn’t worried about his friend-turned-book.

“Like what?”

“Falling over. People push books over for fun, you know.” From the boy’s expression, Matt can tell he’s done that himself. “And if no one takes care of a broken arm or a busted jaw, the book might even die. Or they’ll survive only to wake up mangled and in so much pain they’ll wish they were dead, and with another library nearby they’ll shove more ledge right down their throat, no question. Is that what you want for Crane?”

The boy keeps his fierce eyes on Matt. The eyes are deep brown and warm, despite the anger burning there.

“What am I supposed to do? Just leave her here?” A look of cunning warps his features. “Leave her so you can add her your sex doll collection? Is that what you want, pchanga?”

Matt resists rolling his eyes. He’s faced worse accusations from those who question why he does what he does, who ask why else would he take care of so many comatose ledge addicts?

“Look,” Matt says, trying to sound like he means it, “if you want to drag her home, break a wrist, smash up her face, be my guest. Even if you get her there without a scratch, you realize you’re going to have to take care of her. Force feed her. Bathe her. Do everything for her. You know what. Go for it. Be my guest.”

Matt goes back into Heyman’s, knowing already that the boy is about to follow him. Rarely has anyone taken a book from in front of Heyman’s, and the boy doesn’t have it in him. His grit and attitude, it’s all surface. He’ll storm in and slam the door and demand Matt take care of his friend. Or he’ll abandon the girl and Matt’ll go back out in ten minutes, half-an-hour, when the sun goes down, to find her there. One of the few books whose names he’ll know.

But when he eventually looks up, the boy not having followed, he sees the kid slowly trundling his friend-now-book down the sidewalk. Carefully, he lifts her rigid body, then walks a few steps with her completely off the ground, and before his strength gives out, before he loses his grip, he sets her down gently, oh so gently.

Not that she feels it. Not that she cares. Not that she’ll ever know.

Guilt eats at Matt. He pushes his chair back, puts a sign on the door and the desk letting potential visitors know that he’s in the depths of Heyman’s with the books. He goes to do the rounds, picking up a bag of fresh cleaning rags along the way. The only visitor on the ground floor is Joking, quietly tick-ticking his information requests to a book whose particular specialty is the history of the Topoi. The book—an old man with skin so leathery it could be used for binding a paper book—ticks answers back, his clicking teeth mimicking almost exactly the lamppost’s language. Matt can’t help thinking of a chattering skeleton.

He skips a room filled with soft, one-sided conversation. Anna talks to her wife Veronique every day, for hours, probably thinking that everything she says is heard, as though her loved one’s just in a coma, not gone. Anna’s face is hard, making her look more like architecture than a person, but when she talks in there, when she thinks she’s got privacy, her entire being softens.

And Matt can’t stand it. He finds himself hating Anna, and hating Veronique even more for leaving Anna behind.

For the next few hours, Matt cleans up after the books, bathing, mopping, changing clothes as necessary. Ledge slows down the metabolism, so this day-to-day care isn’t as strenuous or as time-consuming as most people think, but it’s enough to occupy his mind for at least a little while. Eventually, though, all the work’s done so he goes back down to the front desk. The register shows a dozen visitors, half of whom have already left again. He recognizes all of the signatures except one, which annoys him to no end. He hates when aliens just come in as though this place belongs to them, as though the human books are just a resource, not living things.

A rub steps away from the wall, startling Matt. The alien’s eraser-textured skin undulates like liquid, as though it’s flowing through the air instead of walking. Two dent-like eyes form in what it has for a head, a giant pushing thumbs into a ball of clay. Its entire body looks like the alien’s trying to pretend to be person having only ever seen a human being once through the wrong end of a grease-smudged telescope.

“Is this you?” Matt asks, pointing to the unfamiliar signature. He doesn’t even bother to be pleasant, which makes him pissed at himself and, strangely, even more pissed at the rub.

“I am that.” When the rub speaks, its voice is a bad copy of Matt’s own, all the life squeezed out of it. “I have arrived for a book.”

“Of course you have.”

The rub pauses, clearly unable to process what Matt’s last statement means. Then its eye dents fill and deepen again in a slow blink.

“I have arrived for Judica Bendtsen.” The rub says the name in a different voice, clearly mimicking someone else. “Can you take me to Judica Bendtsen?”

Matt doesn’t trust himself to speak, not even to just say, “Yes.” The alienness of the rub makes its request sound like rightful ownership. All of anger and guilt in his heart he doesn’t want to think about, and opening his mouth might bring it all out, and this rub wouldn’t care in the least, Matt’s emotions and words no more momentous than the angle of the light falling on the buildings outside. Completely irrelevant to the matter at hand.

Matt opens Heyman’s index, checking out of habit to make sure no one else is using Bendtsen at the moment. As with most books, her specific specialty is rarely used. In Bendtsen’s case, she’s a great resource for galactic fashion as well as all that’s known about those races in the outer reaches of the known galaxy.

The rub follows Matt soundlessly, making it seem as though he’s walking through Heyman’s alone, searching for his own book to read. People sometimes ask him if he ever opens the books, but he just tells them no. He doesn’t tell them he’s tried ledge and after having the entire Central Galactic Archive in his brain, he’s fine with being ignorant, because at least that ignorance is his own.

But walking through Heyman’s sometimes feels like he’s trespassing on a graveyard, the ghosts of the dead visible, just waiting for the living to disturb them. The eyes of the books slip open sometimes—even though he tries to make sure they’re closed so that the membranes don’t dry out—so he’ll turn a corner to find confused eyes fixed on him. They aren’t confused. They aren’t fixed. But it’s hard to convince his subconscious of that.

Matt stops in front of a middle-aged woman with long dark hair he can’t ever get into a tidy ponytail, so strands flit to either side of the book’s face. She’s been on ledge so long her face is gaunt and spare, though it’s still apparent how handsome and imposing she must’ve been at some point. With her eyes closed, she seems to be sleeping.

That is until the rub asks the book a question in a language that sounds like someone pounding a rug free of dust. The book answers in an approximation of the same language, the mouth so distorted in its effort to match the alien tongue Matt’s afraid the book’s jaw will break. It hurts to listen to the sound, and it sickens him to watch.

He can’t help thinking of Haifa.

He took ledge the first time because she was into it and he wanted to please her. He wanted to do at least one thing that would make her happy. She praised the mind-expanding properties of the drug—not mentioning that it’s actually mind-extinguishing. Matt could never figure out if that’s actually what she wanted: the null of meditation, the egolessness of Zen. She was one of those who accepted ledge so readily into the body she lost herself for weeks on the tiniest bite, and with each hit her time under its influence grew and grew until he wasn’t living with her, he was living with furniture.

Two hermit crab scholars knocked on his door one day and offered to take care of her. Exhausted, he said yes, and they carried her away, taking her somewhere outside of the human ghetto, though he didn’t know that’s what they were going to do, didn’t understand what he’d agreed to until days later. By then there was no trace of her, and he couldn’t identify the hermit crabs except by calling them hermit crabs, and hermit crabs, like most of the aliens on the Inside-Out, tend to look the same to human eyes.

He is halfway into a bottle of whiskey when the rub is standing in front of him again, but this time Matt’s not startled. Not until he notices that beside the rub is the book, Judica Bendtsen.

“I like to check out this book.”

Stunned, Matt wonders where it even learned that phrase? But the wonder only lasts a second before anger overtakes it like a flash flood.

“You can’t take her from here.”

“This book is fashion expert. I need for business.”

“She is a human being.”

The rub shakes its head in a mockery of assent. “Judica Bendtsen is a book.”

Matt’s standing without even realizing it. Somehow, the rub has noticed the change in Matt’s attitude, that something is wrong. Its eyes fill and re-excavate.

In that mockery of Matt’s voice, the rub says, “I will pay. Money can arrive. Many things can arrive.”

“This is not a store!” Matt’s voice is a roar.

Aping him, the rub yells back, “This book soon will die. I will rebind.”

“No. Fuck no. Get the fuck out of here.”

The rub says, “But I arrive here for Judica Bendtsen.”

Matt puts one hand firmly on the book and the other on the rub, or he tries to. As his hand gets close to the alien, its body retreats. He uses this to his advantage, advancing on the rub until it’s forced out of Heyman’s entirely, and then he slams the door in its face.

The rub stands there. It knocks on the door politely.

Matt turns the lock.

The rub tries the handle.

Matt stands there until the rub leaves.

Only then does he take the book back to its place. It takes a good twenty minutes of stopping and starting, lifting the unwieldy body, and it’s only halfway back he realizes the book is in a different position. Did the rub get the book to walk to his desk? Was the alien right that Judica Bendtsen is dying? What did it mean by “rebinding”? Does he have the right to make decisions for her, for any of them, even if they can’t decide for themselves? Or was taking ledge that decision?

The rest of the whiskey waits at his desk.

Night’s fallen. The streets outside are dark except for a burning trashcan crawling down the far sidewalk, picking at odds and ends with its boneless limbs. Joking is the last visitor out the door, bending his body towards Matt in a genial nod, but Heyman’s doesn’t really ever close, because Matt can’t ever really leave. If he left, all the books inside would be abandoned, and even those few with relatives would fall into ruin, the minds left to die in bodies they no longer need.

Would he be to blame? Why is this his responsibility?

A knock at the door.

It’s the boy from earlier, probably back to return the book, now that he understands what having a book means. Of course, Matt expected this, but the fact that he ended up being right doesn’t make him feel triumphant, just tired. He opens the door with his best approximation of a welcoming smile.

“I need your help,” the boy says, his eyes feverish.

“Sure, I’ll take her off your hands.”

“No, pchanga.” The boy shakes his head violently. “She’s my yannow, not yours.”

“So what do you need me for?”

“Look, hume, I asked around. You do this all the time with your little museum of the living dead here.” The boy takes a deep breath, working himself up to say, uncontrite, unapologetic, “I need your help. I’ve stashed her in my house. She’s warm. I’ve put blankets on her. But she hasn’t changed at all. She doesn’t do anything but stand there.”

The boy stops talking. Matt knows exactly where he’s been, and where he’s going, but he lets the boy say it. The boy chews on his lips. The boy is determined not to let his voice break.

“What do we do now?”

The next day, the boy shows up around noon and Matt shows him the ropes. Here’s the register. Here’s the index listing all the books. Here’s the list of living relatives. Here’s the record of how long each book’s been under, and how long they’ve been at Heyman’s. Here’s all the equipment needed to run the place. Here’s contact info for all of Heyman’s suppliers. Here’s what to do if a book gets violent, which happens only occasionally, and you shouldn’t worry since at that point they’re generally too weak to harm you, more a danger to themselves.

The boy’s name is Mamood, but Matt can’t stop thinking of him as the boy. He’s convinced he’s just going to disappear as soon as he’s confident he can take care of his book. Matt doesn’t blame him for this, he just doesn’t want to make the effort if it’s going to be wasted.

For the boy’s part, he won’t stop calling Matt pchanga, though Matt suspects the term is said a little more friendly than before.

The next day, Matt takes a lunch break, leaving the boy in charge. The boy hasn’t brought Crane to Heyman’s, which only reassures Matt that his hunch is right, that the boy’s knows all he needs to know, he’s going to ditch out. But he might as well take advantage of the extra help while he’s got it, and today’s advantage means taking the train to Little Beijing and eating noodles and pork while it’s daylight out and the crowds are swimming and he can feel normal for the first time since before Haifa first tried ledge.

He wonders where she is. And whether she’s been rebound. The rub said it as though it happens so often it’s actually a thing. And Matt has to admit, he doesn’t know, it might be. He doesn’t keep up with the technology of the Inside-Out and the discoveries human scientists are slowly making about how their new world works.

Matt knows there are other places like his where books are held. There’s a section of the Bright Hem where books are settled among the trees and grass, placed out in that wilderness as though in a giant sculpture garden. A hospital in New New York is dedicated to studying ledge, and so books are there as research subjects, a non-unappreciated side benefit being that the books can provide research on themselves via the CGA.

But he has no contact with any of them directly. He’s sealed himself inside a hermetic little world where he’s the only one responsible, the only one who cares enough to do anything.

And where he doesn’t know enough to do anything.

The noodles and pork turn as tasteless as the glop he feeds the books. He sits there until the broth goes cold watching the people and aliens walk by, all of them with somewhere to go and something to do, or at least the illusion of it.

When Matt returns to Heyman’s, the boy isn’t at the front desk and the door is unlocked. The books are unprotected. Matt counts the hours he’s been gone and figures that if the boy left soon after Matt left, then he needs to make the rounds. The books may not care if they wallow in their own waste, but it eats Matt up inside to think about it.

Cleaning rags in one hand and a bottle of sterilizing solution in the other, Matt walks through Heyman’s only to stop when he hears a conversation. He recognizes Anna’s soft patter. The other voice is the boy’s, his tone gentle. Matt can’t hear exactly what they’re saying, but he can tell when the boy asks a question, followed by the long spill of sounds that’s Anna’s answer.

Looking around him, he sees that the books have already been tended to. He stows the rags and sterilizing solution back in the closet. On his desk is the day’s Daily Record, the crossword partially filled in. Today, all the clues are meaningless, the alien words truly alien, as though the paper itself doesn’t understand what’s printed on it.

After the boy goes home, Matt stays at his desk and waits. Usually he turns the lights off and heads to his bedroom in the back of Heyman’s, but he’s looking for something tonight, something he thought he saw last night, and now he’s desperate to see again. He opens another bottle of whiskey. He thinks about smoking, something he hasn’t done since Earth. Tonight he wants all the vices inside him.

An hour into his vigil and two glasses in, he spots it. The rub. It glides across the sidewalk in front of Heyman’s. It notices Matt sitting at the desk, but doesn’t act concerned. It tries the door and the door opens because Matt didn’t lock it. The rub enters and heads toward the main section of Heyman’s, then checks itself and moves to stand in front of Matt’s desk instead.

“I arrive for the book,” the rub says.

“I know.”

Even with the distortion of the rub’s voice, Matt thinks the two of them sound almost identical. A few more decades, a few hundred bottles of whiskey down the road, and that’s his voice. He’s hearing the future from this alien seer.

“You said you can pay.” The rub attempts a nod. “Can you pay in information?”

Two hours later, Matt is erasing Judica Bendtsen from Heyman’s index. In his pocket is a dat-book with all the information he needs to find Haifa. He leaves a note for the boy, telling him everything he might have forgotten to tell him in the past two days and tucks the master keys into the top drawer of the desk. He weighs the note down with an unopened bottle of whiskey and a fresh glass. He doesn’t know if the boy will stay, but it’s the kid’s responsibility now, and Matt thinks he’ll stay, and suspects he’ll do a better job than Matt ever did, which is more than Matt can hope for.

The trains through the human ghetto run all day and night. Matt assumes that’s the same throughout the Inside-Out, but he hasn’t ever left the ghetto to test that assumption out. He stands on the platform waiting for the next cross-ghetto train and adjusts his backpack. Everything he owns or cares about is in there, except Haifa. He’s not used to carrying so much. His shoulders already ache, but he feels lighter than he has in years.

About the Author

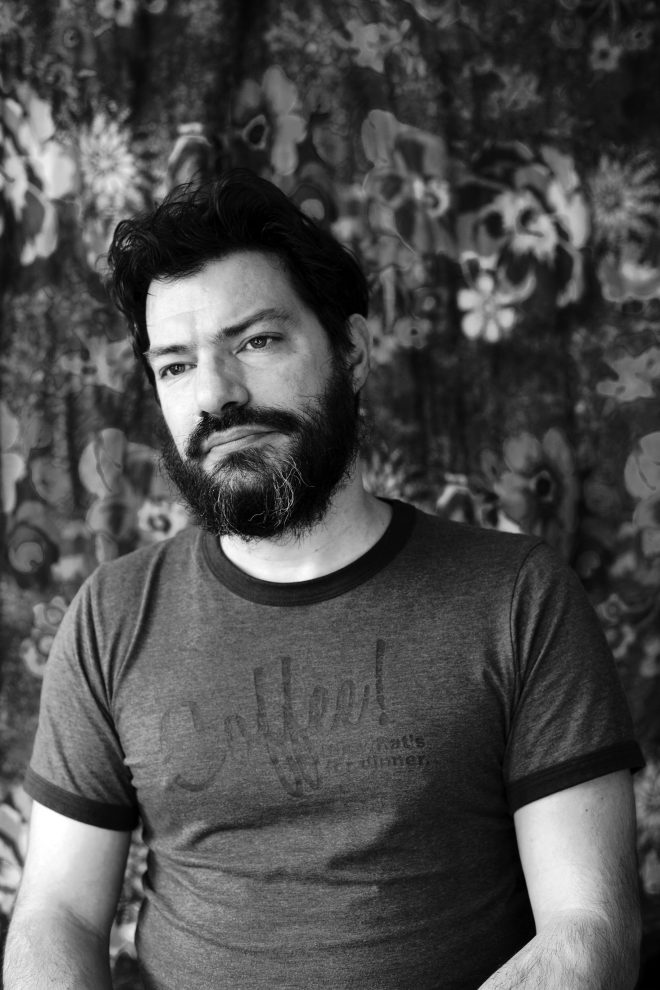

Andrew Kozma

Andrew Kozma’s fiction has been published in Albedo One, Drabblecast, Interzone and Daily Science Fiction. His book of poems, City of Regret (Zone 3 Press, 2007), won the Zone 3 First Book Award. He currently, and for the foreseeable future, lives in Houston, Texas.

About the Narrator

John Meagher

John is the writer/narrator of Tales of the Left Hand, an ongoing fantasy series offering “swashbuckling, intrigue, and a dash of magic.” Links to audio, print and ebook formats of his books are available at www.talesofthelefthand.com. In his secret identity, he’s a graphic designer living in Northern Virginia with his wife, daughter and two cats.