Three Dragons, Three Tattoos: a review of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (Part 2 of 2)

The following article contains spoilers for both the novel and filmed versions of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. It contains discussions of adult material contained in both. Reader discretion is advised.

This is the second part of a two-part article.

#

Casting and Characterization

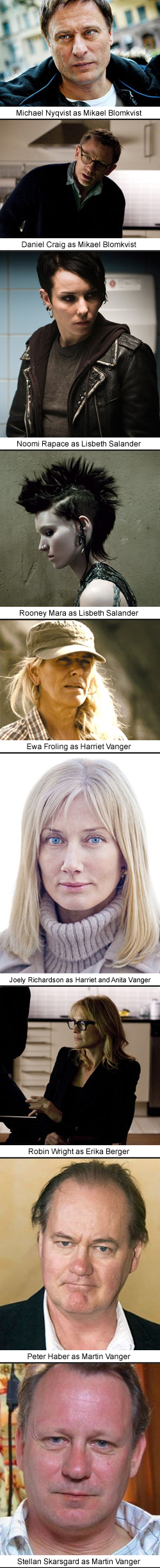

The two main characters in the film are Mikael Blomkvist, a 40-something disgraced journalist convicted of slandering a major financier, and Lisbeth Salander, a 24-year-old genius with a dark history and a major problem relating to people.

In the Swedish version, Mikael is played very seriously by Michael Nyqvist. He really looks like a journalist — he’s not glamorous and he doesn’t dress well. He exercises, he cooks with his nieces, and he has some genuinely amusing lines in the film. To me, he seems a full, well-rounded character.

In the Swedish version, Mikael is played very seriously by Michael Nyqvist. He really looks like a journalist — he’s not glamorous and he doesn’t dress well. He exercises, he cooks with his nieces, and he has some genuinely amusing lines in the film. To me, he seems a full, well-rounded character.

In the American version, Daniel Craig — best known to American audiences as James Bond — portrays Blomkvist. Because Craig is… well, let’s be honest here… pretty darn studly, it’s up to both the actor and the director to make him appear more like the Blomkvist of the novels. As such, Craig affects mannerisms that Nyqvist didn’t have to — he wears his glasses around one ear when not using them, and he rather ostentatiously uses what looks like a Moleskine notebook.

I’d have to give the edge to Nyqvist in the case of Mikael’s character — because he gets the look down, he doesn’t have to affect mannerisms. Also, when he celebrates, he looks much happier about it than Craig; I don’t think I’ve ever really seen Daniel Craig look happy when he’s acting.

As for the other main character, Noomi Rapace (Swedish version) runs away with it. Rapace is small, skinny-but-muscular, and very expressive. Even when her face is shut down to emotion, it’s still quite clear what Lisbeth Salander is feeling. In all ways I found her more believable than Rooney Mara.

Mara, who was until this film probably best known as the sister of Kate Mara (American Horror Story), gets the look down pretty well, although a lot of that has to do with costuming and makeup. I think, unfortunately, Mara’s portrayal of Lisbeth suffers from writing and directorial issues. In the novel, Lisbeth has had a tough life, but she still has emotions; in the American film, Lisbeth only has anger and diffidence (and, at the end, sadness).

I think the biggest difference in their characters is the way they play the “holy crap, Martin’s the killer” scene: Mara’s Salander does rush to save Mikael, but Rapace’s really makes me think she cares about him. Again, writing and direction — even during the sex scene, Mara seems disconnected, whereas it’s very clear (via acting) that Rapace’s Salander enjoys the hell out of sex. (Mara does have a great line late in the American version during another sex scene, but even then it’s more like she’s using Blomkvist than they’re sharing something.)

One portrayal I want to also pay additional attention to is that of the adult Harriet Vanger (hey, I told you the articles had spoilers). Although in both cases she only had a limited amount of screen time, the reveals the actresses had to… um… reveal… made it important that a talented actress was cast. And, because of changes made to the ending in the American version, they had to look vastly different as well.

In the Swedish version, Ewa Froling had to look like she’d lived for forty years in the Australian outback, and she did — she was still blond, but her face was weathered and tanned. Because of that appearance, I’m sad to say that I couldn’t get over how silly she looked even as she discussed being abused by her father and brother. This is the actual ending from the novel, by the way.

Joely Richardson, portraying Harriet in the American version, was more convincing to me as Harriet. First shown as pretending to be Anita Vanger after the real Anita’s death, Harriet was revealed to be a financier living in London. She looked more like the girl who played 16-year-old Harriet than Froling did in the Swedish version. Again it comes down to writing — and probably the need to not marginalize the role for a well-known actress like Richardson, as well as avoiding expensive location shooting in Australia (or somewhere that looks like it).

Other important actors and characters in the film:

Erika Berger — Mikael’s on-again-off-again lover, played by Lena Endre (Swedish) and Robin Wright (US). My biggest problem with the American version here is that Berger is not supposed to be glamorous — and Wright plays her just as well as Endre did. The issue is with the casting of Craig; he seems too glamorous for the likes of Wright, who is made up to look like your average 45-year-old woman who’s worked all her life at a difficult job (journalism is hard; trust me). I believed Nyqvist and Endre more than Craig and Wright.

Henrik Vanger — Here I give the nod to Christopher Plummer (General Chang in Star Trek VI) over the Swedish actor Sven-Bertil Taube. Plummer simply emoted better than Taube, especially at the ending; Taube’s acting occasionally seemed forced. I will give Taube a slight edge in the beginning because, instead of appealing to Blomkvist’s journalistic instincts, he appealed to his memories: in the book, both occur, but only in the Swedish film is as much attention paid to his connection with the Vangers (as a boy, Harriet and her cousin Anita used to babysit Mikael).

Martin Vanger — This one is pretty much down to the writing and usage of the character. In the novel, Martin was relatively low-key until it was revealed that he’s a killer. The Swedish version (Peter Haber) was more faithful to the book in the build-up, whereas in the American one I think more foreshadowing of Martin’s activities gave Stellan Skarsgard more to do. Also, Skarsgard simply got to be more evil in the final sequence than Haber — again, writing. Advantage: Skarsgard.

Beyond those four, I had occasional issues with some of the characters, but overall everyone else was in the background. Christer Malm, Dirch Frode, Cecilia Vanger, and Plague weren’t too big on the stage. It was nice to see Goran Visnjic as Armansky, despite the small role — he’ll have more to do in the sequels. There is, however, one more character worth noting, and I think you know who I’m talking about.

THE Scene. You know the one I mean.

In order to really understand why Lisbeth was put in a situation where she could be raped by someone in direct authority over her, people who haven’t read the book need to know the following: when Lisbeth was twelve, she tried to kill her abusive father by lighting him on fire. This led to her being institutionalized, and her mother also ended up in a facility (I believe she had some sort of catatonic disorder). After her release, Lisbeth responded to bullying and violence at school with violence of her own. As a teenager, she committed small crimes and was also seen in the company of older men. She was already under guardianship because she wasn’t an adult, but she remained in that situation even into adulthood because, in Sweden, that’s how the social system is. Once a person has a guardian, that person is legally charged with assisting their ward in whatever way he or she needs.

In the case of Lisbeth, her guardian had been Holger Palmgren — in the American version, this is the person Lisbeth plays chess with, and who she finds on the floor having suffered a stroke. Palmgren, as Bjurman states in his moment of exposition, had let Lisbeth have free reign over her life and her finances (in the novel, it’s explained how Palmgren formed a positive relationship with Lisbeth and that she cares for him… at least as much as she cares for anyone). Bjurman, however, believed that Palmgren had not had Lisbeth — someone whose records indicated a mentally-disturbed and extremely violent individual — on a short enough leash. So far, Bjurman has not done anything wrong, per se — again, as Lisbeth’s legal guardian, he has to do what he believes is best for her.

The three Bjurmans are very different, though. In the novel, after being forced to perform oral sex, Lisbeth investigates Bjurman and finds that, other than what he did to her, there’s no dirt to dig up. In the Swedish film, Bjurman (Peter Andersson) is a little older, but both Bjurmans are portrayed as good-looking single men. In the American version, since being fat automatically equals being evil, a heavier actor (Yorick van Wageningen) was cast. Also, in the American version, Bjurman has children, whereas in the other two he does not. All three behave the same way once they decide to take advantage of Lisbeth, though, and the oral sex scene is pretty much the same in all three.

When I went to see the film, my friend Will said he’d heard the second rape (the one in Bjurman’s apartment) was more brutal than it was in the Swedish film. I wasn’t quite sure how that could be pulled off, since in both films Lisbeth is beaten, bound, and raped. (I noted with somewhat-clinical distraction that both Mara and Rapace scream more or less the same way.) The novel indicates that Bjurman engages in anal sex with Lisbeth, something not explicitly discussed in the Swedish film (although afterward Lisbeth does limp home — which occurs in all three versions). The American version makes it particularly explicit by having Bjurman actually say what he’s doing.

Lisbeth’s “recovery” from the rape is different when comparing the book and the two films. The book is very clinical — in it, Lisbeth retreats into herself, staying in and taking painkillers and sleeping until she feels capable of fighting back. The Swedish film is similar — the limp home, the pills, the cigarettes. The American film is more explicit, showing Lisbeth breaking down in the shower, washing away the blood from the attack. While more powerful, the final scene shows something we never see Lisbeth do anywhere else in the film, and to me that makes it less consistent with the character — especially given the Asperger’s tendencies Mara (and the writer and director) gave the character. I’m more likely to believe Lisbeth turning inward than expressing her pain via tears.

The revenge scene is also similar across all three presentations, although the kicking of the dildo doesn’t occur directly in the book — she kicks him, but not there. It’s much more threatening in the American version than the Swedish, being metal instead of plastic or whatever as well as much larger. In all three she shows him the video; in all three she makes her threats; in all three she tattoos him.

The threatening scene in the elevator, by the way, is exclusive to the American version.

(If you skipped the discussion of the rape scenes, here’s where the article continues.)

Final Analysis

Should you go see the American version of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo? I’d say yes: it’s a well-made film with decent acting and a coherent mystery plot. But I think that, to really get the full impact, you need to sit down and read the novel first (or, failing that, right after). The novel is tough to read — it’s very clinical and dry in many places, but it’s not boring. At least, not after the first hundred pages or so.

Should you go see the American version of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo? I’d say yes: it’s a well-made film with decent acting and a coherent mystery plot. But I think that, to really get the full impact, you need to sit down and read the novel first (or, failing that, right after). The novel is tough to read — it’s very clinical and dry in many places, but it’s not boring. At least, not after the first hundred pages or so.

I also think you should see the Swedish version of the film, if for no other reason than Noomi Rapace’s excellent portrayal of Lisbeth. Once you see the Swedish film, you’ll probably want to watch the second and third ones, and read the second and third books in the series as well. (For my money, the second book is probably the best of them, only slightly edging out Dragon Tattoo.)

Given how much money the American Dragon Tattoo made ($76 million — the budget was $90 mil, and I expect it to hit that number soon enough), and (more importantly) how much buzz it received, I’d be extremely surprised if there aren’t adaptations of The Girl Who Played With Fire and The Girl Who Kicked a Hornet’s Nest in the next year or three.

I just hope they’re a little more faithful to Lisbeth’s character in future adaptations. With the American version of the film, Fincher, Zaillian (the screenwriter), and Mara have pretty much locked us into a certain portrayal of our hero. Unfortunately, that portrayal isn’t quite as accurate as what Stieg Larsson intended when he wrote the book. He didn’t want Lisbeth to be an emotionless machine who sometimes gets angry; he wanted her to be a fully-rounded character. In the Swedish film, she is so much more than what Mara played her to be. Maybe we’ll get that the next time out.

#

Note to Parents: These films — and the book — contain graphic violence, explicit language, explicit sex, and rape. I usually say you should use your own discretion when it comes to your children, but I hope that, in this case, I don’t have to.