Escape Pod 881: Wild Geese

Wild Geese

by Lavie Tidhar

With rustling wings the wild geese fly

Round fields long strange to hand of toil

Called by the officers in charge,

We labour on the desert soil.

—Trans. from the Shijing by James Legge (1871)

With the end of summer the wild geese appeared, heralding the changing of the seasons. In the bazaars on the outskirts of Ulaanbaatar the usual crowds of Silk Roaders engaged in ever more heated commerce. Soon it will be winter: ice and dust storms, and the train crews grumbling and swearing on the tracks, and any sensible hobo would be long gone, to work out the winter as far south-west as possible. Now boots and fur coats made their grand appearance on the stalls of the Naran Tuul, and Silk Roaders from Tehran and Yekaterinbug, Gdańsk and Dushanbe argued bitterly with each other and haggled over wholesale prices, shipping berths and train routes.

Efrem knew they would soon be gone. Traders were like wild dandelion seeds, ubiquitous and easy to take flight. Efrem, who rode the rail to Ulaanbaatar from Yiwu the year before, considered themselves almost a local at this point. Now they chewed on a khuushuur and contemplated the chase.

The first wild goose of the season had been spotted, somewhere to the west of Dalanzadgad.

Efrem had worked the whole of the previous year round the railway terminus, doing odd jobs if and when those materialised. They’d exchanged small-denomination money for travellers passing through, turning Martian shekels into tögrög and Drift salt into vatu. They’d hired out as an interpreter for an old Swahili trader from Dar, did the accounts for a local dress shop, served goat stew from a stall to the railway porters, helped fix domestic robots in a makeshift repair stall, and ran errands for anyone with cash to spare. Hobos usually didn’t stay this long in one place. But Efrem knew here was their best chance to see a wild goose. So they stayed, and waited. And now one had materialised, out in the desert.

“We’re hobos,” Avi argued when Efrem, excitedly, tried to tell them about the Hongyan’s appearance. “We ride the rails, we don’t go off-track.”

“I’m going,” Efrem told them. “You can come or you can stay, it’s up to you.”

“You’d go without me?” Avi looked more offended than hurt at the thought.

“We’re hobos,” Efrem said. “Sooner or later we always go our own ways.”

Efrem met Avi by the tracks, of course. The railway bulls were chasing Avi at that point. Avi had hopped the train somewhere on the Russian side — when asked, later, they were vague on the details — and made it undetected right up until some autonomous expert system in Ulaanbaatar Terminus decided to order a surprise inspection of the cargo cars. The bulls were Yunnanese robotniks, far from home and miserable with the job. The sand got into their joints and causes havoc with their cyborged parts.

Efrem, who was friendly with a few of them, pulled Avi behind their stall (they were still selling goat stew at that time) and bribed the railway bulls with a couple of free bowls of food and a bottle of camel vodka each.

“What’s so great about wild geese, anyway?” Avi said. Efrem wasn’t very clear on where Avi was from. Avi had augmented themselves, at various times, with numerous additions and modifications, including an organic aug grown from supposedly-Martian bacteria DNA, magnet implants (their one party trick was levitating small objects like paperclips), body-wide bioluminescence (Avi loved lighting up in the bath), a secure sneakernet drive supposedly implanted into their colon and carrying some sort of stolen military-grade code Avi was supposed to deliver somewhere but for reasons of their own never did, a full cyborg left hand with eight spider-like fingers, and retro-mirrorshades that could iris close over their eyes, mostly for decorative purposes but useful when there was a sandstorm.

Efrem said, “I thought a Hongyan would be exactly your sort of thing, Avi.”

“I like people,” Avi said. They shrugged. “That’s definitely one thing you don’t get with a wild goose.”

“So stay, then,” Efrem said, trying not to seem hurt and failing.

Avi drew them closer.

“I like you, though,” they said. Efrem had to smile back at them.

“So you’ll go?”

“Sure,” Avi said. “But come winter I’m heading to the Drift and as far away from here as possible. My magnets don’t like the cold.”

“Your magnets.”

“They’re very sensitive!”

Efrem laughed and pulled Avi to them, and then there was no more talking for a while, as sand gently beat against the window glass.

#

The hot wind whispered in Efrem’s hair. They clutched the control bar of the glider. Efrem realised they hadn’t flown a Gullfire since Leningrad, and that felt like a lifetime ago. Or was it a Nightwing? Efrem could no longer remember. There was a dusty road far down below but no vehicles. Animal skeletons, bones bleached white, littered the ground. A reminder that living things died in the desert.

Avi was to their left. They screamed laughter, and the wind snatched their cry and tossed it to all corners of the Gobi.

Efrem held on to the control bar and glided over the desert. The glider was a part of them. Efrem was plugged in through crude backstreet sockets. They were never noded as a child, and only got the old Lorq sockets on a whim one drunken night in Samarkand. They weren’t good for much, other than to plug into obsolete machines, old tractors and the like. But this glider was old, the wings patched many times over, and Efrem could feel their body in the air, their wings turning, and they swooped over the old abandoned road with wild joy.

The desert was huge. The miles flew by below and the day lengthened by the time they saw a roadside ger in the distance. Efrem shouted to Avi, who hollered back, and together they swooped down low.

The ger looked abandoned. There was a water harvester outside, and solar panels strewn haphazardly on the sand. Efrem, who was tired and thirsty and hot, shrugged at Avi. They shrugged back and went in.

Inside the large round tent it was dark and cool. A short person in a blue desert robe materialised and gestured them to sit down. Efrem ordered in broken Mongolian, and the owner – at least, Efrem assumed it was the owner – fired up a wok. Two plates of hot mutton noodles materialised shortly after.

“Where are we even going to sleep?” Avi said. “Did you think about that?”

“I packed a tent,” Efrem said. “Have you never gone off-track before?”

“Not if I could help it,” Avi said. “It’s the rails for me, all the way round the world and back again.”

“How far did you get?” Efrem said.

“Zanzibar. You?”

“The Spiral.”

Avi whistled. “They let you in?”

“I’m respectable, me,” Efrem said, and Avi laughed.

“Worked in the hydroponics gardens there for three months, deep in the Down and Out,” Efrem said. “But it’s weird in the Drift, and the Spiral, well… they always need workers, but just as long as we stay in the deeps. So I bailed and drifted the Drift for a couple of years, but I never went down below the thirty-line again. I decided I wasn’t really cut out for life underwater.”

“Can’t blame you,’ Avi said. ‘But still. I’d like to go one day. Just ride the rails all the way down to Hainan and then… I don’t know. I guess the railway stops once you hit the ocean.”

“How come you never went?” Efrem said, curious.

Avi shook their head. “Some bad business with a dolphin with a bug up their ass. I’ve been keeping strictly to land ever since.”

“Well,” Efrem said with unshakeable logic, “there are no dolphins in the desert,” and Avi laughed.

In the end they spent the night in the ger, huddling close by the central woodstove. Early in the morning they caught thermals and rode on until the landscape changed and they could see lakes in the distance, and shortly after came cow herds and wild horses. Efrem stared enchanted at the horses, who were still free, only here of all the places of the Earth. They sailed above them and came at last to the city of Dalanzadgad.

They checked into a hotel near the power station on the outskirts of town. Efrem was restless to keep moving. The Hongyan was out there, leaving a trail of dust in its wake. Soon it would vanish again, if they couldn’t catch up to it.

But they and Avi were not the only guests that day. Efrem observed with dismay the arrival of several large, tanned, well-equipped travellers who rode in on two brand-new Shenzhen-made wind-up jeeps. Australians or Martians, it was hard to tell which.

But clearly they, too, were here for the goose.

“We’ve got to get a move on,” Efrem said, frustrated. “How many more Hongyan hunters are coming down here?”

“You knew we couldn’t be the only ones,” Avi said.

“And look at all their equipment!”

Avi grinned at Efrem. “But they’re fancy folk,” he said. “We’re hobos. Come with me.”

They extended their spider-hand. Efrem stared at them.

“Where to?”

“Somewhere there’s a frozen river in the middle of a desert,” Avi said. “Somewhere, the sand dunes sing. Are you coming, or what?”

Efrem took their hand. The spider fingers grasped their hand and pulled her along.

Outside the hotel, and parked next to the two wind-up jeeps, was a beat-up old van with more pockmarks than the lunar surface.

“Ivan, it’s us!” Avi said.

“Hop in, then!” the van said in Russian. The doors slid open. Efrem waved their hand in front of their face.

“It smells disgusting!”

“Ivan’s ex-Buryat Spetsnaz,” Avi said. “From when the Buryat were fighting for independence.”

“It was a long time ago!” the van said.

“How did you end up here?” Efrem said.

“How did you?’ the van said rudely. “Are you coming or not? If you want to catch a wild goose you have to get up early in the morning, as they say.”

“As who says?”

“They say,” the van said. Efrem sighed and climbed in. Avi climbed in after them and the door slid shut. The van, with a screeching of tires and a shower of sand that went all over the parked jeeps, shot out and away from the city.

“There are bottles of water in the back,” the van said. “And some tins and foodstuff. All part of the service.”

“Do you have toilet paper?” Efrem said.

“Toilet paper?” the van said. “What do I need toilet paper for?”

Efrem sighed.

“What do you run on, anyway?” they said.

“Nuclear.” The van cackled, a sound like static. “I can go on forever. Now shut up and let me drive.”

Efrem closed their eyes.

“Where did you find this one?” they murmured.

“It’s good to have connections,” Avi said.

The van sped into the desert.

#

There is no sky like the sky under the Gobi, which goes on forever. At night, camped under the stars, only the embers glowing in the fire, Efrem could see the firefly lights of low-orbit transports and the jewelled countenance of Gateway and the other, smaller orbitals in the sky. The shadow of the giant spiders crawled along the surface of the moon, and beyond, too far to see, the solar system teemed with human life.

But Efrem saw the stars, which are distant beyond compare: the whole of the Milky Way spread out across the sky from one horizon to another. Only the slow, giant Exodus ships left for the stars, and who was to say if any would ever reach them?

They fell asleep at last, under all that alien light, and Avi snored beside them.

#

In the morning they went on. Ivan cursed in strangely archaic Russian, the wheels churning dust. They came to the Yolyn Am and stopped, and Efrem and Avi walked on the frozen river within that gorge, with steep rock walls rising on either side of them, and they chipped the ice and filled their bottles and rode on. They saw the miles of singing sand dunes in the distance, and the snow-peaked mountains that rose beyond, but they didn’t stop, and Efrem never got to hear the sand dunes sing their mournful wordless songs. Ivan drove like a maddened machine. Efrem wondered how many they’d killed in the war.

They rode on and on and there was no road. They no longer camped but slept in the van, and the van never slept. Efrem, tossed left and right by their passage on this rough terrain, began to wonder at Ivan’s motivation. They ate dried noodles, salted peanuts, cold tinned stew. From time to time they’d come to curious heaps of stones left in the sand like shrines. Ivan said they were called ovoos. Some were small, some large and decorated with blue silk scarves. Once, they found a grinning camel skull placed beside the stones.

Ivan circled each ovoo three times and then stopped, insisting Efrem and Avi did the same. They always placed a new stone on the ovoo in their passing, as was custom. Sometimes they left small offerings behind, too: some chocolate, a shot of vodka, a small bottle of snuff.

Efrem began to measure out the distance by the ovoos. They were the only sign of other people having been there before them. The desert swallowed people up. It offered silence. Twice they came to small rivers and saw gers in the distance, with children playing in the shallows and camels feeding on the grass, but they didn’t stop.

Then, one morning, a week after they’d left Ulaanbaatar, Efrem woke up and saw, far in the distance, a storm cloud of dust. It hid whatever lay beyond the horizon, and they knew then, with rising excitement, that it was the wild goose.

#

They saw it in the distance as the van burst through the dust at last.

#

It was as tall as a peak of the Altai, as wide as the Belukha glacier. Its skin was grey, cracked, featureless. It dragged itself across the Gobi sand. Snow caked its upper layers. How could such a monstrous being escape the world’s sight? Yet the Hongyan could vanish quickly as the mist, dismantling themselves just as they built, burrowing in hidden places where they slumbered deep, sometimes for decades, before re-emerging to transform the world.

Unlike its tamer siblings, the Hongyan roamed free. Efrem stared enchanted as it moved across the landscape, like some Soviet era concrete statue of a turtle, perhaps, blown up to an impossible size. It was not in truth one thing, but several moving in tandem. The parts of the Hongyan kept shifting and adjusting loads, pistons moving, drills burrowing, mixers turning, whole internal factories churning as they laid down a city.

Ivan stopped. Avi was silent beside Efrem. The lumbering creature towered ahead of them, slowly making its inexplicable way onwards.

Behind it rose the city it had laid.

Efrem stared at the towering walls of the city, the pristine new skyscrapers, chrome and glass shining in the sunlight. High bridges as graceful as swan feathers spun the towers. A residential neighbourhood to the west of the city rose in mute sand-coloured blocks all close together, apartments ready to be moved-in to, empty shops and kiosks waiting down below. The Hongyan laid down wide avenues and city squares. It planted parks, and decorated the city with gaily-coloured signs and street lights.

The city lay there, untouched by human hands, slumbering in wait.

And Efrem realised the city was almost complete.

“The wild geese fly about and light, amid the marsh, where grain once shone,” Efrem whispered. “We rear the walls as we are told. Five thousand feet are quickly done.”

The van rocked. “Great is the toil, and sore the pain,” Ivan said. “But peaceful homes will rise again…”

“You know the poem?” Efrem said, surprised.

“I have an enormous database,” Ivan said. “Do you want to see it?”

“Rude…” Efrem murmured. Ivan chuckled to themselves. The van started up again, but they moved slowly now, as though weary of spooking the Hongyan.

The three of them crept along a trackless road towards the nameless city.

#

It was farther away than it appeared. The van rode on the tracts left behind by the Hongyan. The desert had been swept clear under the slither of that behemoth. Nothing survived on the outskirts of the city. The Hongyan did not build roads. It just made cities.

Such wild geese were rare. And they were old. The original machines had built cities to order across the Chinese mainland and Siberia, but that was decades if not centuries past. One still existed outside of Irkutsk, no longer working, a permanent exhibition and museum all in one. Efrem had visited once: had climbed into the bowels of the maker, made their way through passages that used to shift and change as the machine rebuilt itself to suit its purpose. Some people even lived inside it now. They’d colonised abandoned factory floors and rooms inside manipulator arms as large as rocket ships, grew potatoes and sorghum in the vast acres of the machine, made homes, made children, whole generations living and dying within that single edifice.

The machines were a product of the old age, before humanity took to the seas and the skies in search of real estate. Now people made their habitats deep in the Drift or high in the Up and Out, on Mars and beyond. The old makers broke down or were salvaged for parts, and almost none remained intact but for the museum piece outside Irkutsk.

Yet some of the machines… broke free.

How or why no one was sure. The wild geese… mutated inside. They migrated to the barren lands and dust bowls where no human lived. Their cycles were unintelligible to anyone watching, but no one was watching. No one remembered them. They hibernated for years or decades before some impulse deep within them sent them on their path again, and they would hunt for some suitable place and erect upon it their creation. Then they would vanish once again, not to be seen until a new generation had all but forgotten them.

“I don’t think we’re alone,” Ivan said.

Fear closed on Efrem’s heart and squeezed. They had to be the first, they had to have it!

“Where?” Avi said.

“Due north. They’re coming at the—”

“The goose,” Efrem said. “Oh, no.”

“Yes.”

“Who?” Avi said.

“Your friends from Dalanzadgad, I think. Hold on.”

The van made whirring sounds. Then a wall lit up and turned into a screen.

“I didn’t know you could do that!” Efrem said.

“What you don’t know could fill – no, let me rephrase that,” Ivan said. “What you do know can fit in the memory on my washing machine and leave plenty of room.”

“You have a washing machine?”

“And submarine capabilities and a couple of nuclear warheads, yeah.”

“But you didn’t think to get any toilet paper.”

“What do I need toilet paper for? Use your hand, Efrem. It’s what evolution’s made hands for.”

“That’s disgusting,” Efrem said, and shuddered, and the van cackled.

The images on the screen were fuzzy at first. Efrem figured Ivan was using a couple of drones which, again, they didn’t know Ivan had. But then they were ex-Spetznaz, so it made sense. They tried not to think about the nuclear warheads.

Dust at first, then two blurry moving shapes that resolved into no-longer clean or new, yet still familiar wind-up jeeps.

The Martians or Australians from the hotel.

“Where are they going?” Efrem whispered, horrified. The camera rose into the air and turned, and Efrem saw the Hongyan.

“Get out of there!” Efrem screamed at the screen. “Get out of there!”

“They can’t hear you,” Ivan said, but gently.

“Why are they going there! You never approach a Hongyan from the front! Surely they know that—”

“They’re lost,” Ivan said. “They don’t know.”

“Can’t you warn them?”

“I’ve been trying. Their systems are not responding. My guess is they stumbled into the storm and lost their way and the dust trashed their– ouch!”

Efrem cringed. Out of the storm and the sky came an excavator bucket as large as a city square. The two jeeps raced blindly into the sand.

They never had a chance.

The bucket slammed down onto both cars like an open palm squashing an irritating mosquito.

Efrem stared in horror. It was over so quickly. The jeeps just… flattened. With everyone inside them. Then the scooper arm rose, scooped up several tons of dirt as easy as a child lifting a handful of sand, then rose in an arc quicker than Efrem should have thought possible, and swatted Ivan’s drones into oblivion on its way.

The screen went black. Ivan cursed. Efrem, sick inside, held on to Avi. They patted them awkwardly.

“Look,” Avi said.

Efrem raised their head and stared. The city rose before them then. The van left the desert and was suddenly on a smooth asphalt road.

“We’re here.”

The timbre of the wheels changed and the van stopped rocking. Ivan yelled in exultation and sped ahead. The city swallowed them, its skyscrapers looking down, and the van was the only moving thing along the thoroughfare of that empty place.

“Stop!” Efrem shouted. They laughed and cried. The van came to a city square. The giant statue of some four-armed general rode on an iron grasshopper in the centre. Efrem and Avi rolled out of the van. Freshly planted flowers formed beautiful abstract patterns in yellows and reds.

“Listen,” Efrem said. “Hush.”

They stood and listened to the silence of the city waiting.

The city waited for its people to arrive. And people might. Itinerant artists at first, or hobos coming off the rails. Nomads will come, and stay a while and marvel at the place, then leave. Their cattle will eat the grass and the leaves on the tree. The city generated its own water and its own power. It would stand there, patient, waiting, for a year or a decade or a century. Waiting for its people to come.

But they, Efrem, were the first.

“I can’t hear anything,” Avi complained.

“I can hear everything,” Efrem said. They laughed. “We need cloth! Do you have a shirt, or…?”

Avi reached into one of their pockets with the cyborg arm and brought out a blue scarf. “Will this do?” they said. “It’s a khadag, I picked it up in Dalanzadgad just before we left. Meant to give it to you before, only…”

“It’s perfect,” Efrem said, and kissed them. They held the ceremonial scarf. It was silk, and light, and painted the colour of the sky above the Gobi. Efrem went to the statue of the four-armed general that the city had generated for itself. Sometimes, the cities the wild geese planted could be a little bit weird.

Efrem tied the scarf to the general’s upper left arm, which was pointing to the distance. The sun was setting now. Far ahead the Hongyan lumbered on, putting the last of the outskirts of town into being. Soon it would be gone into the mists, and only the city remain.

Efrem made sure the scarf was tied securely.

“I claim you, on behalf of hobos everywhere!” they shouted into the sky. A startled sand martin took off into the air with a beating of wings, the only other living creature there.

Efrem took a bow. Ivan honked their horn and Avi clapped. They looked up at them and smiled.

“Do you get to name it?” they said.

“Yes,” Efrem said. “But not for a while.”

They stepped down and took Avi’s hand in theirs.

“Let’s go home,” they said.

“Home where?” Avi said.

Efrem swept their arm across the darkening horizon. Lights were coming on in all the buildings. Millions of apartments, all waiting for their occupiers.

The city had been lonely here. It needed people.

And then its people came.

Efrem smiled at the city and murmured, though only Efrem could hear it. Then they turned back to Avi and threaded their arm through theirs.

“I’ll let you choose,” they said.

Host Commentary

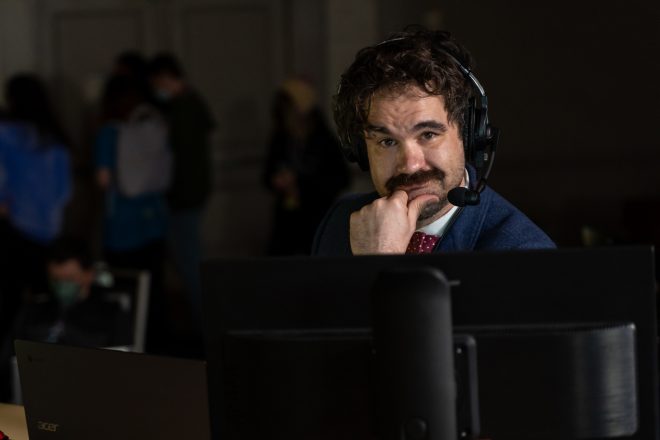

And we’re back! Again, that was Wild Geese, by Lavie Tidhar, narrated by Kyle Akers.

I loved how this story was so joyful and full of hope. We are solidly in the future, and it’s a bit grungy and lived-in, but there is still magic. There is still the random chance magic of Efrem and Avi finding each other, and there is the magic of chasing wild geese, which are giant ancient beings, laying down remarkable, random cities, complete with statues of four-armed generals riding iron grasshoppers. And the random chance magic of Efrem and Avi being the sort of people who drift around, finding life and delight in wherever they happen to be, means that they are here now, for the creation of this new, empty city. The first. (Well, them and Ivan the van, of course.)

I would think that there wouldn’t be enough people here for Avi, who loves people, but then Efrem immediately personifies the city as being lonely and needing people, too. So perhaps that will be enough delight for all of them, for awhile. And when it isn’t anymore, I fully expect these two (with or without Ivan) to continue to drift around, finding their own future magic.

Our opening and closing music is by daikaiju at daikaiju.org.

And our closing quotation this week is from Mary Oliver, because I love her own poem Wild Geese, and this seemed to be perfectly appropriate:

“You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert, repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.”

Thanks for listening! And have fun.

About the Author

Lavie Tidhar

Lavie Tidhar’s latest novel, Central Station, is out now to rave reviews. He is the author of the Jerwood Fiction Uncovered Prize winning A Man Lies Dreaming, of the World Fantasy Award winning Osama, and many other books and short stories. He lives in London.

About the Narrator

Kyle Akers

Meet Kyle Akers, a versatile talent from Kansas City, Missouri, who’s worn many hats throughout his journey. His journey has seen him take on various roles, from touring the nation as a musician with the electro-pop band Antennas Up, gaining recognition through television placements, to becoming a respected voice actor featured on The NoSleep Podcast, Pseudopod, Audiobooks, and more.

Recently, Kyle embraced a new role as a full-time ICU nurse. On top of that, he serves as a Host Volunteer Co-Coordinator for Games Done Quick, where he actively contributes to their charitable mission. Kyle’s life story is a fascinating blend of music, storytelling, healthcare, and philanthropy, all wrapped up in one unique individual.