Escape Pod 451: The Aliens Made of Glass

The Aliens Made of Glass

by Helena Bell

Sister Charles Regina, formerly of the Daughters of Perpetual Help, attends to her boat, the Nunc Dimittis, as if it were the sole member of her parish. She scrubs the white transom, the gunwale, the wooden steps leading to the bridge, and the metal railings. She vacuums the carpet in the salon, empties then refills the refrigerator and checks the interior cabinets for ants. Once a week she cleans the bottom of the hull and even in this she is practiced and ritualed, reciting a dozen rosaries in time with the digs of her paint scraper, the bodies of barnacles swirling around her like ash. It gives her peace. Each action and inaction she commits will lead to consequences and she revels in the knowledge that everything worn away will be built up again. In these moments she does not miss the convent or her religion or God. She does not mind that the aliens are coming.

Sister Charles Regina, née Kathleen, brings the dock-master filets of tuna, wahoo, mahi mahi and sheepshead. For this and her company, Gray gives her electricity, use of the slip, and help with the lines. They watch the evening news together, and Gray does not ask about her lack of prayer over the meal. Kathleen does not ask after his parents or sister. He is her family; she is his. It is enough.

“The aliens passed Neptune today,” the local weather girl says, but she has been announcing the passing of Neptune for several days. A countdown glows in the right-hand corner with flickering dates and estimations. They will be here in 467 days, three years, or seven years, decades, soon, soon, sooner than we are ready.

The aliens move as slowly and perpetually as shadows on a sundial. The anchors express disbelief that we spotted them near Pluto at all. Should not they have zipped in at the speed of light? At warp? Hyperspace? Should not they be in our skies one minute, the valleys of the moon the next? Kathleen wonders if space is more like the ocean than anyone thought with currents and tides and troughs. She pictures the aliens adjusting a compass set to the pull of opposing suns. She imagines long, bone white fingers turning the knobs of a LORAN adjusted for eleven-dimensional space.

Instead of sports, a man in a checkered suit announces the decision of all space-faring nations to reroute their shuttles, their satellites, and refitted weather balloons. Like marathon racers or a soapbox derby, the line of them stretches from Baikonour to the moon. A tech company has announced a prize for the first privately-funded spaceship to reach the aliens. A second prize for the first to establish meaningful contact. A third for the first to determine their intentions and draft an appropriate response.

The checkered man begins to stutter, his face reddening under the studio lights. He misses basketball and baseball, where the most threatening stories were coaches throwing metal chairs across the gleaming laminate floors. He takes a deep breath. He has a job, a purpose; his world is not so different that he has forgotten to be professional. “Whether the prize will be in currency or fame or nonperishable foodstuffs is unknown at this time.” He smiles and hands off to a field reporter at a local high school. The seniors intend to build rockets. They do not expect them to reach the aliens, or orbit, or the upper levels of the atmosphere, but on each rocket the students will write a message in any and all languages in which they have proficiency. English, Latin, Spanish, German, French, Klingon, Elvish, Binary. . . They no longer care about prom or AP English exams, but of a future filled with higher-level mathematics.

“I have an old Celestron NexStar 8 on the roof,” Gray says. “If you’d like to watch them later.”

“Maybe,” Kathleen says.

One by one the charter boat captains trickle into the store to exchange gossip and squid lures. The border to Virginia has closed again; the price of butter has tripled. The Coast Guard is checking their passengers and the passengers’ driver’s licenses more frequently. The captains still regard Kathleen with some suspicion, the crispness of her habit and the smoothness of her hair as it disappears under her blue wimple, but Gray says she’s all right. He slips his hand below the table, pinching her like they did when they were children. She’s all right.

“How about a sermon, then?” they say, but Kathleen has none to give them.

“I have one,” Gray says. “My great-great-grandmother named her first child AO because he was supposed to be the Alpha and Omega. The first and last. Don’t remember how many she ended up having, but she got down to YZ. . .”

The captains remember their own stories about AO. He was shot by bootleggers. He could spit with his mouth closed. To Kathleen it seems that they must all be related, each descended from the same common ancestor, and she feels alone save for Gray’s hand on her knee.

On Sundays Kathleen takes charters out past the Knuckle Buoy and into the Gulf Stream. Her passengers signal to other boats, and there is an exchange of packages. Sometimes they are small, and sometimes they are in the shape of people. Kathleen stands on the bridge staring out over the gray slate of ocean and thinks this would be a good place to die. Her body would be worn away and only her bones, tumbled and smoothed, would wash upon the shore, indistinguishable from sea glass and stone. She would be put in jars and glued to some picture frame. Her clavicle would shadow two children reaching out to a manatee. Nunc dimittis servum tuum, Domine. Now dost thou dismiss thy servant, Oh Lord.

Not all of her would make it, like the rockets arcing up past the water tower, the Outer Banks. Her appendix and tibia may float endlessly in the currents alongside messages the children have written. Arma virumque cano Roanokeae qui primus ab oris Americanum.

This would be a good place, she thinks, where, if she died, she would still exist.

Even at sea Kathleen wears a white blouse, a wool skirt, stockings, and brown orthopedic shoes. She stands and speaks with austerity and meets the Coast Guard’s Kodiaks with her registration papers, commercial fishing license, and the requisite number of life jackets.

The officers lean their guns against the Captain’s chair and sigh. The world is changing, yet they are bored. Kathleen offers them prayer cards and rosaries made of sea glass. She feeds them Starburst candies and fresh lobster tail while her passengers huddle behind her.

“The state barely has enough corn and hog farms to feed itself. We need a miracle, not more northern immigrants,” the officers say.

Kathleen smiles. “There will be enough. There is always enough if you are not greedy.”

As the Coast Guard leave they tell her when the next tanker will slip into port, which will be her best chance to refuel. “We will watch out for you.”

The passengers wave after them. “It is a miracle,” they say.

Kathleen does not go to church. Churches still exist, but not in the way she remembers. The Catholic chapel she attended as a child is now Episcopalian. And instead of evensongs and Eucharists, the call and response of prayer, the newly faithful discuss the merits of scientific revision. If aliens exist, then God must exist as a highly-intelligent life-form. The aliens may know of him. He may have angles and evolutionary biology. This is the moment they have dreamed of, the thing which has kept them away from religion all this time: the inconsistencies between faith and science may finally be resolved. We will know.

Kathleen does not doubt the reverend’s credentials or sincerity. He knows the guitar tabs for all her favorite hymns and volunteers with the displaced college students. They in turn help feed the elderly and homeless. She brings them fish and passes messages to other boats when they ask after their families. She understands the reverend’s anxiety, his desperation to take on as many roles as he can. An idea is like a virus, catching and adapting. Until we know, the aliens are both hostile and friendly. They are destructive and magnanimous. In Rome the College of Cardinals sends dark smoke into the air again and again. Sometimes Kathleen doubts they are voting at all. She suspects they are holding the crowds steady with the ecstasy of sustained anticipation.

The aliens send no signals. They do not respond to radios of varying frequency, but it does not stop people from trying. Kathleen turns from station to station as individuals with their own VHF, UHF, and CBs call out again and again.

Come in peace, some beg.

Others: Can I interest you in a timeshare in Florida?

Others: Go the fuck away you fucking green-skinned monsters before we fucking blow you to fucking bits.

Kathleen fishes. She dives the wrecks and spears grouper and flounder. She drives her boat far enough that she cannot see shore and drops her anchor into the sand. The aliens do not represent mystery to her, but an end to mystery. These were the words of her first Mother Superior: If God exists, he is in a box. Do you open it?

This would be a good place to die, she thinks, in between the deep swells where only parts of her will survive. And she will go knowing that she does not know.

The aliens can barely be seen. They emit no light, and astronomers claim they can only track them because they are numerous and wide.

“Are we sure they’re even aliens?” the reporters ask.

“They move with such indecipherable acceleration and determined trajectory to be inconsistent with any other possibility,” the scientist says. The counter flickers less and less. 422 days. 400. 365.

A man in Pitt County invents vertical farming. He stands in front of soybeans growing like an abacus: glass tubes filled with vines stretching like a skyscraper over his fields. His wife sighs and says she told him he could only grow what wouldn’t bother the cows. People need cows.

“The aliens will be so proud of me,” the man says, and his wife nudges him. “Of us. Look at what we can do!”

By the time the aliens pass Uranus and Saturn, the farms have spread to Missouri and New York, then Europe and Asia.

Borders reopen; there is white smoke in the air.

“If the aliens meant us harm,” Pope Alexander IX says, “they would have destroyed us by now. We must be the best of ourselves, so that we may rightfully expect the best in others.”

Gray leads Kathleen up to the roof, and his hand is warm at her elbow as he shows her how to adjust the lenses and magnification of the telescope. A glass plane of wheat stretches between the condominiums, and as the wind whistles past, it is almost like singing. Kathleen closes her eyes, for it is more beautiful to her if she does not know what causes it.

“My great-great-uncle AO,” Gray says, “could speak every language. Sometimes I think it’s him out there, reminding us he’s still around.”

Some nights they are joined by the reverend and his band of students, the charter boat captains and their wives who peer through spyglasses and homemade imaging devices.

“My great-great-uncle AO,” one says, “could see farther than any man living. They say he could see his brother drowning from two counties over. Bet he could count the aliens through their windshields from here.”

Kathleen stands apart from Gray, but his hand follows her. She does not know how she is expected to respond to him with the captains and the reverend and the astronomers all around. “I think I’ve had enough,” she says.

The next morning Kathleen splices rope and cleans bait. She opens the bellies of wahoo and mackerel and tuna. She knows what is inside each of them. She knows the world was not built in seven days, that Noah and Abraham and Enoch could not live to see their grandchildren’s grandchildren’s grandchildren. When she casts the net for mullet, she catches the detritus of homemade rockets, messages scraped along their sleek, gleaming flanks. She tosses them back without reading; the messages are not meant for her.

When she drives into port, Gray is there on the finger pier, arms open. He kisses her hello and goodbye and thank you for all the fish. She does not mind so long as they go no further than they did as children. She lets him sleep in the stateroom with her, in a separate berth, and nudges him out the door when it is time for her to cast off the lines.

She drives past the rock jetty, the Clifton Moss, the Hutton. She knows the way to tell she is on a collision course with another ship is if the angle between them does not seem to change, only the distance. Gas becomes more soluble in liquids at cold temperatures, and that is why a warm coke fizzes in great spurts when it is opened after a day in the sun. Wahoo will strike at anything so long as it flashes brilliantly.

When the sun sets, Gray stands between two tackle-boxes, hooking the rope around the cleat. He steps onto the transom in perfect timing with the reversal of her engines. He knows where to stand, where not to stand, and how many times she must wipe the salt from the windows before she will come to bed.

The television announces the aliens and human spacecraft will enter the asteroid belt at the same time, separated only by the tumbling girth of the Themistian family.

It has been two years since Kathleen’s last confession to a priest. It has been two years since she and the other nuns packed their bags to drive home to their families. It has been two years since the aliens were spotted hanging onto the shadow of Pluto’s orbit like remoras.

The Nunc Dimittis runs slower and slower, and Kathleen knows soon she will have to drive it up the New River and into dry dock. Gray wishes she would hire a crew or cease to take on charters, but she refuses to yield.

She can handle the boat by herself, and there is beauty and discipline in reaching only so far as your arms allow. When one of her propellers bends, she dives into the marina to fix it herself. She knows it will break eventually, just as she knows the inevitability of long months on shore. She finds comfort in the thought that when her boat rests on the long metal beams, as men peer inside the engines and replace gaskets, she will paint the hull the blue of her old wimple. Everything worn away will be built back up again. It gives her peace and clarity, like the burst of shoreline above the crest of ocean swells.

She delays out of fear, of uncertainty whether Gray will ask her to move into his cottage, and what she will say. It is only acceptable to indulge the part of herself that is in love with him so long as there is another part committed to the deep mysteries. She must hang in the balance or not at all: carry her rosary, wear wool skirts and stockings that itch the backs of her legs. Gray watches her dress in the morning and remarks that looking like a nun and being one are not the same thing.

“Yes,” she says.

“I had a great-great-uncle named YZ,” Gray says. “One night he was on a ferry boat that started to sink. Everyone else got into the life rafts or jumped into the river to start swimming, except YZ. He was still on the deck, swaying with all the whiskey he’d drunk. They called to him from shore, dripping wet and alive and he called back, ‘The captain goes down with the ship!’“

Kathleen wraps her hair in a blue scarf. “It is time for you to go,” she says.

Gray unwinds the rope from the cleats and steps off in time with the forward thrust of the engines. “Some of us are going into town tonight, to watch the aliens on the drive-in screen. Think you can dock by yourself?”

“Yes,” she says.

The ocean is glassy and calm, and if Kathleen were brave enough she would climb up to the tuna tower, feeling every bounce and dip as she sliced through the water. No one has ever reinterpreted the ocean. The amount we know is less than what we know we do not know. The Hutton, the Aeolous, the Monitor, the U-352—all could begin to ascend, and we would not notice until the black breach of their bows.

Kathleen is contemplating how the ocean may be less like space than she previously thought when the fish in her hands flips at an inopportune moment, pulling himself off the gaff and driving the six-inch leader into the peach of her ankle. She screams, but there is no one there to hear her. Twice on the way in, the bilge pump alarm sets off, forcing her to hobble down the ladder and back up again. She does not pray, but calls out again and again on the radio:

“We are hurt, we are hurt, we are hurt.”

The Coast Guard Kodiaks stop her as she passes the hook of Cape Lookout. A young man cradles her in his arms, lifting her from one boat and into the other. They leave the Nunc Dimittis in their wake.

It drifts and drifts away, and Kathleen accepts that it will sink before she can return.

These are the things the hospital has in abundance:

Aspirin; foley catheters; extra-long twin sheets; elderly patients who have lost most of their hearing and control of their bladders; nurses, doctors, and medical students; disposable, sterilized scalpels in small plastic bags which crinkle with the sound of a thousand parakeets.

These are the things the hospital does not have in abundance:

IV antibiotics; strawberry-flavored Jell-O cups; men named for their great-great-grandfathers; satellite cable reception; cigarette lighters; wooden pews in the small, nondenominational chapel two floors below Kathleen’s room.

The only thing that tells Kathleen it is a chapel at all is a small stained glass window under which Kathleen examines her vow of poverty. Without her boat she has only one wool skirt, one blouse, one pair of stockings, and a blue scarf soaked in her own blood. She has a roommate, Agatha, to whom she gives the bed by the window despite the nurses’ protestations that Agatha is nearly comatose from her stroke. She also has vases and vases of flowers, all from Gray, and at night she plucks the petals one by one so they float down like multi-colored barnacles. Offshore, Kathleen’s rosaries and bibles, the jars of sea glass and photographs of her parents will sink slowly to the sand to be picked over by sting rays and small tropical fish. Sand tigers will feast on whole-wheat bread, slices of ham, dark chocolate squares. They will nose open the bait-well to find the arched fish who could not escape, long dead and beginning to rot.

Kathleen worries that the hospital is so careful of her because the Coast Guard told them she is a nun. The nurses frequently change her IVs, her bandages, and bedding, and Kathleen fears there is some other woman in the hospital with a fishhook wrapped around her tendon and to whom they say amputation is the only answer.

News that there is a new patient spreads, and soon Kathleen has visitors crowding around her bed and asking her to play bridge, to go dancing, to gather in the lounge with them to watch the aliens. When Gray meets them he introduces himself as Kathleen’s boyfriend, and she does not correct him. Some of the nurses raise their eyebrows, but they are Episcopalians and Baptists, Presbyterians and Methodists. “Perhaps the rules have changed, considering,” they whisper.

The satellites and shuttles were not designed for dramatic changes of course or evasive maneuvers, and they crash into the lone asteroid between them and the aliens, despite the vast emptiness of space. It is almost a miracle, Kathleen thinks.

The aliens emerge unscathed, moving together and apart like schools of fish while the broken pieces of the world’s space programs are pulled into their wake.

“Maybe the aliens won’t take it personally,” the patients say. “We can build new ships, better ships. The aliens will help.”

Statisticians fill the news reports with corollaries and theories: if the world economy was previously buoyed by a belief in hell, then now innovation will be spurred by impending contact with a new collective imagination. We commit to solar and wind, to biofuels and static electricity.

The aliens will teach us sustainability; we will learn the secrets of species introduction and the prevention of invasiveness. “We must still be good,” they say. “So good. The aliens will not speak to us until they are sure we are ready for their gifts.” Religious leaders across the globe reconcile with one another. “Love thy neighbor.”

There are still demagogues and the fearful, cults and reformations, but they are fewer and farther between. It is so much better to be hopeful and happy. The hospital chapel is always empty; the world has found its new god.

Though the nurses claim she is mostly gone, Kathleen believes she can hear Agatha wake in the middle of the night. She believes Agatha rustles and turns in her bed, then walks to the window to stare out at the stars.

“Thank you, Lord,” Agatha whispers, “for the time I have had, for the days that it rains, and for the days it does not rain, for yellow barley, the yellow corn, the yellow squash waving like a summer dress outside my window. I am ready to die when you are ready to take me. It is okay if you have forgotten, I will wait.”

When the nurses come in the morning Kathleen asks that they see to Agatha first. To change her bedpan and her frayed nightgown, to brush her hair away from her face to keep it from itching.

“Why? She doesn’t know where she is or what’s going on. You’ll have this room to yourself soon,” they say.

“Please,” Kathleen insists.

Gray brings Kathleen apples and chocolate to add substance to her frame. She splits them with Agatha, lining up the fruits on her bedside table in increasing order of size. Gray asks Kathleen to marry him, and she says no less and less fervently.

One day Kathleen pulls the pins from her hair and puts on a floral blouse she traded with another patient. She goes to the cafeteria to discuss astronomy and quasars with the reverend and his roving band of volunteers. They ask her to teach Latin in their tutoring circle, and she agrees, translating the Aeneid with young cancer patients who have an appropriate respect for both the past and future.

“Nec tibi diva parens,” she recites. Your mother was not a goddess. “Per-fide, perfide.” Faithless one, faithless one.

At night when she is startled awake by the nurse’s cart or the wind, she hopes she will fall back asleep quickly. A few more hours, she hopes, while beside her she hears Agatha pray for patience, for forgiveness. “And thank you, Lord, for the crash of waves in the air, for the lambent sky, and for the aliens made of glass.”

The aliens pass the moon, the upper reaches of the atmosphere, and all televisions fill with pictures of their ships.

“They are ships, yes?” the anchors say, and everyone agrees. Of course they are ships. We had dreamed of lights, of titanium hulls and gleaming rivets, of details pulled from a century of humanity’s xenoconsciousness, and though that was not what drifted down through the skies, “They are ships,” the anchors say. We have charted the progress of aliens. Their ships are a permanent and irreparable condition.

Kathleen and the other patients plan to head to the beach for the moment of the aliens’ arrival. Kathleen is thinking it would be a good place to say yes to Gray, when the nurses stop her in the hallway.

“Your roommate,” they say. “Is awake.”

“Then let’s bring her along,” she says.

Gray and the nurses and the ambulatory patients and Agatha and Kathleen pile into vans and buses and drive out to the beach. The ships, mere geometric indentations in the clouds, drift lazily over the ocean.

Kathleen and Agatha walk the edge of the shore collecting scotch bonnets and sea glass, limpets and sand dollars, things to hold and count in their hands. Agatha leans into Kathleen, her steps slow and hesitant as her body comes back to her. As Agatha regains her footing, Kathleen feels herself getting lighter, as if they are part of the same wave, a seiche, one falling as the other rises.

“You’re a nun?” Agatha asks.

Kathleen nods. “I was.” Kathleen asks if Agatha would like a priest to hear her confession, if there are any sacraments she has missed during this long illness that she would like to recover.

“No,” she says.

Kathleen asks if she would like to pray, if she would like to recite the psalms or discuss scripture.

“No,” Agatha says.

Kathleen asks if she is scared for the future, if she would like Kathleen to find out about her children or brothers or nieces before the chaos of the aliens’ landing.

“No, thank you,” Agatha says and leans back to stare up at the sky, counting the ships. “They’re so beautiful,” she says.

Kathleen stares out over the ocean as if waiting for a rocket to wash up at her feet. Nunc dimittis servum tuum, Domine. Quia viderunt oculi mei salutare tuum. Now Thou dost dismiss Thy servant, O Lord, because my eyes have seen Thy salvation. But there are no signs to be seen.

Gray and the other patients prop a small portable television in the dunes. They watch as the ships lower and lower towards the oceans and the open fields, preparing to land on the highways that have long been emptied.

“I don’t suppose,” Agatha starts, and Kathleen leans in, prepared to give her whatever it is she asks. “You would like to say a prayer. If it will make you feel better.”

“I have none,” Kathleen starts, but Gray is reaching into his coat pocket. He pulls out a package wrapped in blue wool.

“It was all I could salvage,” he says, handing it to Kathleen. She pulls back the fabric to find dark stained leather smelling faintly of mold. “I almost didn’t want to give it back to you, ruined as it is.”

“It’s beautiful,” she says. It is stiff in her hands, the pages peeling and cracking as she tries to open it. There is no gold cross or other decoration, only her name written in a small, strange script, in the lower right-hand corner. When she asked her mother why the word of God must be written in books, why it could not be known instantly and forever by everyone, her mother said that faith was like a human and an alien meeting for the first time. Without mutual cultural reference they stare into each other’s eyes and do not fall in love.

Everyone is quiet, their bodies turned towards Kathleen, their eyes watching the small color television, their ears listening for the whir of motors overhead. Kathleen wraps the bible in her old wimple and folds it into her lap.

“I once knew of a man named YZ,” Kathleen says. “He was riding home on a ferry boat which began to sink.”

The news anchors begin to count down as the ships lower and lower all around the globe. 9. . .8. . .7. . .

“As everyone swam or rowed away, he heard the ship cry out: I am abandoned!”

6. . .5. . .4. . . The police threatened bodily injury to any who crossed the barriers or fired upon the aliens.

“YZ ran his hands along the wood and the railings, the sweat-stained wheel. In his last moments he pressed his palms upon the deck—”

3. . .2. . .1. . . the ships hit the ground—

“and whispered, I am here.”

—shattering into billions upon billions of pieces of bright, wind-smoothed glass.

About the Author

Helena Bell

Helena Bell is a poet and writer living in Raleigh, North Carolina where she is an MFA candidate in Fiction at NC State University. She has a BA, another MFA, a JD, and an LLMin Taxation which fulfills her lifelong ambition of having more letters follow her name than are actually in it. She is a graduate of the Clarion West Workshop and her fiction and poetry have appeared in Clarkesworld, Shimmer, Electric Velocipede, the Indiana Review, Margie Review, Pedestal Magazine and Rattle. Her story “Robot” was a nominee for the 2012 Nebula Award for Best Short Story.

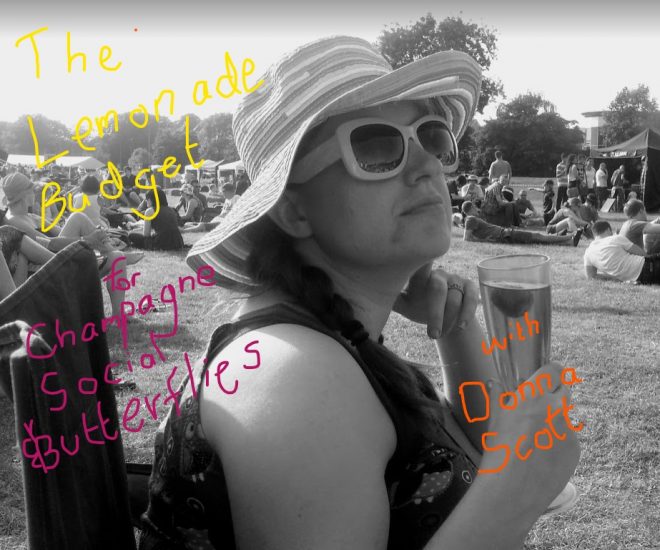

About the Narrator

Donna Scott

Donna Scott is a writer and freelance editor, specialising in genre fiction. She has worked with Immanion, Angry Robot, Games Workshop and many independent presses. She was also the editor for Alan Moore’s novel Jerusalem. She is the editor of Newcon Press’s Best of British Science Fiction series. She is an active member of the British Science Fiction Association, having been Awards Adminstrator from 2009-2013, and Chair from 2013-2019.