Escape Pod 282: You’re Almost Here

Show Notes

A&E are offering us a prize pack for a random drawing! So US residents, please email feedback at escapepod.org and put CONTEST in the subject line. We’ll do a drawing next week!

You could win both of the following:

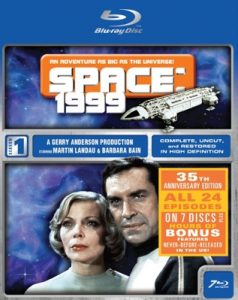

Space 1999: The Complete Season 1

In the year 1999, a spectacular explosion at a lunar nuclear waste dump sends the moon out of Earth’s orbit. In this seminal sci-fi series from producer Gerry Anderson, the men and women of Moonbase Alpha are suddenly propelled on a treacherous journey across the universe in search of extraordinary new worlds.

The Prisoner

Since its CBS debut in the summer of 1968, the masterful British TV series THE PRISONER has captivated American audiences. Now A&E presents a definitive aficionado’s edition of the cult classic which is considered one of the most innovative TV series ever filmed, for the first time in breathtaking Blu-Ray.

Show Notes:

- Feedback for Episode 274

- Next week… The grandfather paradox rears its violent head.

You’re Almost Here

By Melinda Thielbar

“Can I share your table?”

You look up to see your dream girl. Red hair, cream-colored skin, face just a little round, breasts just a little small. Not movie-star beautiful, not perfect just–nice. She smiles, and her cheeks dimple, and you’re in love. You gesture to the empty chair across from you with a grin of your own.

“Be my guest,” you say.

“Thanks.” She takes the chair and sets her coffee cup down. You close the notebook in front of you and open your mouth to say something—anything—to impress this girl.

Without looking at you, she turns in her chair, pulls a phone out of her pocket and bends over it. You watch her face in profile as she slips a pair of earbuds into her ears. Your mouth is still open, so you close it and look away. That’s when you see that every table is occupied. Men in suits, women in suits, a few people your age in khakis or jeans. They’re all looking down at their phones, laptops, or handheld game consoles. Sunlight streams in through the floor-to-ceiling windows, and you watch people passing by on the street for a minute. They’re all looking straight ahead, faces set the way they have to be in a city this size. When it’s this crowded, the only privacy you can give a stranger is not to notice them. That idea interests you, and so you open your notebook to jot it down at the bottom of the second-to-last page. As you’re writing, a chair scrapes behind you, and a guy in a navy three-piece moves past. He flips his phone open and then closed again, checking the time, and hurries out.

The girl across from you moves almost as fast as he does. “Thanks,” she says and flashes that amazing smile again before she grabs her drink and hops to the newly-open table. You write FUCK across the top of the second-to-last page of your notebook, tuck it into your pocket, and go get another coffee.

The barristomatic (you call it this; no one else does), takes your thumbprint and opens a menu with your recent drink selections. They’re supposed to be sorted so the one you drink most is at the top. For you, it might as well be random. You do something different every time. This one’s a half-pump vanilla, half-pump strawberry, soy milk latte with a lousy espresso bean that still costs more than all the other ingredients put together because it’s fair-trade and organic. You once enumerated every combination, ranked them from most to least expensive and calculated how long it would take to try all of them. Assuming they add nothing to the line-up (unlikely), you’ll have to live to be eighty (likely) and drink four cups a day (near-certain). The machine hisses out your espresso and steamed milk. The menu pops up a new screen “People who enjoyed this drink also liked…” You hit Done and taste your drink. It’s perfect and artless.

You turn around and see someone sitting in the chair you just vacated. It’s a guy in jeans, probably another unwilling table-sharer. He’s sitting inches away from the red-haired girl. They’re practically back-to-back, both bopping to whatever’s playing through their identical earbuds, and neither one’s aware of the other. The guy’s t-shirt reads: “Steal This Shirt”. You put a lid on your coffee and head out the door.

Across the street a city train rattles into an elevated station. You consider getting on it. There’s always a seat, and you can use your phone to access your desktop at home. The outside of each car is basically a giant flatscreen, each showing a different full-color ad. The first has a woman’s face, larger-than-life, with skin like the girl in the café and eyes like a dead doll. The words “Feel as beautiful as you are” write themselves across the picture, and the model’s face dissolves into a prescription bottle. Lines of text pop up all around it “I’ve never felt better!” “More energy than my ten-year-old.” “Answered prayer;” each is date and time-stamped less than a minute ago.

On the second car, a thirteen-year-old boy points a magic wand toward the viewer, and the words Harry Potter and the Voyage of the Dawn Treader run across the top in gothic script. The wand emits a stream of colored lights as you watch, and the words “Stunningly original”—New York Times appear in sparkling relief. You turn away, dumping your half-full coffee cup in a trash can, and head toward your apartment and your computer and the day’s work you still have to do. A glance at your phone tells you it’s after 3:00. You have less than two hours.

So you walk, and the train blunders away behind you, and you’re left with the hum of cars making their way up and down the city street. Tiny personal models available in any color– custom-mixed if you like–tricked out with any or all of 200 options. Slots for smart phones and media players come standard. You happen to glance into a car while you’re waiting at a crosswalk. There’s a Seinfeld re-run playing in the steering wheel. It doesn’t matter, you tell yourself as you cross the street, keeping your eyes on the laughing driver nonetheless. The car has impact sensors and automatic route planning; it’s running on a smart road. The driver is cargo 99.9% of the time.

You arrive at your apartment at 3:34 according to the time on your phone, the only time that matters. The stairwell door opens at your thumbprint, and you walk up the four flights of stairs to your apartment. You could take the elevator for $1, and you tell yourself you should do it since time is getting short. You could pay a monthly fee for unlimited elevator rides. If you did, you’d spend your whole day riding up and down–just to make sure you got your money’s worth. Depriving your landlord of an extra $60 a month is more appealing, so that’s what you do, huffing up the steps even now, when you only have 86 minutes left.

You press your thumb against the plate on the front door, and it opens with quiet beep followed by a click. You bounce straight into your chair, kick the door closed, and roll two feet to your desk, grabbing a cola from the refrigerator on your way past. You slot your phone into its dock, and the bulky monitor and keyboard, anachronisms you prefer to projections on your desk and wall, come to life. You wonder how much power these things suck while they’re sitting in standby mode, but it doesn’t matter because you pay for electricity by the month instead of by the use. No way around that. When was the last time someone read a meter on anything? Water/power/internet service–the people who use the most are the winners because everyone gets charged the same.

That thought gets you started, and you’re typing before your WP even loads. The computer remembers the keystrokes, though, and it’s already processing what you’ve put into it. The lines appear rapid-fire, re-shaping themselves as they hit the special program you’ve built into the WP. Every sentence is parsed, keyworded, and searched–a million bytes of information stream back for every one you send. What you say is analyzed and allied with the voices that are already out there. Your WP captures the sound of what they say and shapes your message into the boxes they’ve provided. Your language flows in; their language flows out: processed, hyperlinked, sound-byte friendly, and streaming ready. You don’t even hear the chime when your output hits 500 words.

The final essay comes out to 999, but you hit a space and type a pointless “a” just to hear the airhorn that tells you you’re done. Anything more than 1000 words has to be slashed; anything less than 500 has to be stretched. The database flashes up a blog entry, a list of tweets, and a supplementary 100 words riffing on the theme of pay-as-you-go vs pay-to-play. There’s also some canned quotes and likely reader links. Later in the day, after you’ve supposedly read the comments and thought about it more, the program will find the IDs of readers who sent you the right links, fill them in, and post your addendum. Your phone’s clock reads 4:50 pm.

You hit Send, and the whole data structure goes to your editor, who won’t read it or change it because she’s paid $10 an hour to deal with 50 authors a day. The machine does it anyway. You’re not supposed to know that, and you pretend you don’t because you don’t want them to know about your upgraded pirate copy–your dirty little secret that matches theirs.

You’ve cracked it. You understand language, the thread of public discourse, the art of taking the internet’s gestalt and parroting it back in a way that looks bombastic and feels safe. You understand it so well you were able to teach a stupid machine that thinks only in 1’s and 0’s to do it for you. All it needs is a series of thoughts, preferably ones everyone else has already thought to death, and it creates the theme, voice, and mood they’ll find the most appealing. You get 50% more hits than anyone else on your publisher’s payroll.

You get yourself a drink–Ketel One and soda, plenty of ice–from your closet of a kitchen and write one long sentence, perfectly punctuated, that fills the last page of your notebook. Then you close it and toss it on a pile of identical volumes that sits between the computer desk and the wall. The pile’s up to your knee. You estimate 10,000 words per notebook. Even with the standard loss from editing (you average around 50%), it’s enough for a novel, a memoir, a treatise on the state of things. You could type it into the WP and turn it into a book.

That’s what you did the last time the pile got this high. It was a success by every metric: 600 downloads a day, 48% click-through, 7 days average from download to read, no fewer than 50 daily posts to message board threads. The bonuses for those stats are how you pay for your Ketel One. Besides that, there’s something about the book that makes people want to buy buy buy. Your 0.05% of the pay-per-conversion revenue could purchase an apartment twice this size, a car, an antique espresso machine that would let you tamp the grounds and steam the milk without computerized help–a million little luxuries you deserve as much as anyone.

You tried to sell it as it was, typed it up with a straight WP and edited sentence by painstaking sentence without the computer’s back-end processing. It took you two years. Your editor called it incomprehensible, told you to stick to being $BRUCE. She was right, of course. You didn’t even try to use the $BRUCE AI for the novel. You created the $SARAH AI instead, a synthesis of Austen, Dickens, and the prose of an obscure 21st century fantasy writer known mostly for his poetry, editing, and hair. It took you 6 months to write the program; you had a book deal 3 weeks later. “Stunningly original,” Kirkus Review called it.

It wasn’t your book. It was $SARAH’s. Changing the words changed the meaning in a way you can’t express even to yourself. You’ve upgraded the software. $SARAH’s next book will be more popular than her last, but you can’t make yourself do it. $SARAH and $BRUCE, two wildly-successful writers that are pure fiction, and you’re a bigger fake than either of them. You could be this decade’s O’Connor, Twain, DeLillo, Hemingway. You’re probably just some self-important hack with programming skills.

You’ll never know. Every book you’ve read, every song you’ve heard, every piece of art of every kind that you’ve ever seen has been viewed through the eyes of a commentator, a re-mixer, a pastiche-maker. Nothing in your life has equipped you to recognize an original thought should you have one. Even if you could, you have no language to express it. Whenever you try to say anything, all you hear is the hundred million voices that will chime in to respond, add, comment, change. You have no one to speak to because everyone is too busy talking, and you’re as bad as anyone.

There are 50,273 cafes nationwide, and an average of 1.63 posers with notebooks in each one. You sneer at them, but you’ll never try to write the hard way again. You’ll never buy that espresso machine because you’re afraid you’ll never make anything better than what the barristomatic gives you. You’re glad the girl in the café didn’t talk to you because there is no way to predict what she would say or how you should respond. For your whole career, you’ve written about where we are, where we’re going and who we’ll be when we get there, but you’ll never write the truth.

Why, this is the future, nor are we out of it.

About the Author

Melinda Thielbar

Melinda Thielbar is a writer, teacher, statistician, and student of the martial arts. Manga Math Mysteries, including The Kung Fu Puzzle and The Secret Ghost is her first children’s series.

In 2005, Melinda left SAS to finish a PhD in statistics. She was awarded a VIGRE fellowship at North Carolina State University. This fellowship is awarded to students likely to make a strong contribution to education in the mathematics and statistics field. Again, Melinda earned a fantastic reputation in the classroom. Her statistics lectures and examples were known for their ability to hold her students’ interest—no easy task in a statistics for non-majors class that’s held at 8:00am.

Melinda lives in Raleigh, North Carolina with her husband, writer Richard Dansky, and their three cats. She is currently working on the research portion of her PhD.

About the Narrator

Mur Lafferty

Mur Lafferty is the co-editor and sometime-host of Escape Pod.

She is an American podcaster and writer based in Durham, North Carolina. She is the host and creator of the podcasts I Should Be Writing and Ditch Diggers. Her books have been nominated for the Hugo, Nebula, Philip K. Dick, and Scribe Awards. In the past decade she has been the co-founder/co-editor of PseudoPod, founding editor of Mothership Zeta, and the editor or co-editor of Escape Pod (where she is currently).

She is fond of Escape Artists, in other words.

Mur won the 2013 Astounding Award for Best New Writer (formerly the John W. Campbell Award), and the 2018 Hugo Award for Best Fancast for Ditch Diggers. She’s been nominated for numerous other awards and is always doing new things, so check her website for the latest.