Escape Pod 344: The Homecoming

The Homecoming

By Mike Resnick

I don’t know which bothers me more, my lumbago or my arthritis. One day it’s one, one day it’s the other. They can cure cancer and transplant every damned organ in your body; you’d think they could find some way to get rid of aches and pains. Let me tell you, growing old isn’t for sissies.

I remember that I was having a typical dream. Well, typical for me, anyway. I was climbing the four steps to my front porch, only when I got to the third step there were six more, so I climbed them and then there were ten more, and it went on and on. I’d probably still be climbing them if the creature hadn’t woke me up.

It stood next to my bed, staring down at me. I blinked a couple of times, trying to focus my eyes, and stared back, sure this was just an extension of my dream.

It was maybe six feet tall, its skin a glistening, almost metallic silver, with multi-faceted bright red eyes like an insect. Its ears were pointed and batlike, and moved independently of its head and each other. Its mouth jutted out a couple of inches like some kind of tube, and looked like it was only good for sucking fluids. Its arms were slender, with no hint of the muscles required to move them, and its fingers were thin and incredibly elongated. It was as weird a nightmare figure as I’d dreamed up in years.

Finally it spoke, in a voice that sounded more like a set of chimes than anything else.

“Hello, Dad,” it said.

That’s when I knew I was awake.

“So this is what you look like,” I growled, swinging my feet over the side of the bed and sitting up. “What the hell are you doing here?”

“I’m glad to see you too,” he replied.

“You didn’t answer my question,” I said, feeling around for my slippers.

“I heard about Mom – not from you, of course – and I wanted to see her once more before the end.”

“Can you see through those things?” I asked, indicating his eyes.

“Better than you can.”

Big surprise. Hell, everyone can see better than I can.

“How did you get in here anyway?” I said as I got to my feet. The furnace was as old and tired as I was and there was a chill in the air, so I put on my robe.

“You haven’t changed the front door’s code words since I left.” He looked around the room. “You haven’t painted the place either.”

“The lock’s supposed to check your retinagram or read your DNA or something.”

“It did. They haven’t changed.”

I looked him up and down. “The hell they haven’t.”

He seemed about to reply, then thought better of it. Finally he said, “How is she?”

“She has her bad days and her worse days,” I answered. “She’s the old Julia maybe two or three times a week for a minute or two, but that’s all. She can still speak, and she still recognizes me.” I paused. “She won’t recognize you, of course, but nobody else you ever knew will either.”

“How long has she been like this?”

“Maybe a year.”

“You should have told me,” he said.

“Why?” I asked. “You gave up being her son and became whatever it is you are now.”

“I’m still her son, and you had my contact information.”

I stared at him. “Well, you’re not my son, not anymore.”

“I’m sorry you feel that way,” he replied. Suddenly he sniffed the air. “It smells stale.”

“Tired old houses are like tired old men,” I said. “They don’t function on all cylinders.”

“You could move to a smaller, newer place.”

“This house and me, we’ve grown old together. Not everyone wants to move to Alpha whatever-the-hell-it-is.”

He looked around. “Where is she?”

“In your old room,” I said.

He turned, walked out into the hall. “Haven’t you replaced that thing yet?” he asked, indicating an old wall table. “It was scarred and wobbly when I still lived here.”

“It’s just a table. It holds whatever I put on it. That’s all it has to do.”

He looked up at the ceiling. “The paint’s peeling too.”

“I’m too old to do it myself, and painters cost money. I’m living on a fixed income.”

He didn’t reply to that, but walked down the hall and was fiddling with the door handle when I joined him.

“It’s locked,” he said.

“Sometimes she gets up and goes out for a walk, and then can’t remember how to get back home.” I grimaced. “I can probably keep her here another few months, but then she’s going to have to move into a special care facility.”

I uttered the code word and the door opened.

Julia was propped up on her pillows, staring at a blank holoscreen across the room, unmindful of a lock of gray hair that had worked its way loose and obscured her left eye’s vision. The channel she was on had finished broadcasting for the night, but it didn’t make any difference to her. She was content watching the flickering gray cube.

I ordered the bedlamp to turn on and gently pinned the hair back up. Now that the room was illuminated, I could see our son staring at it. The holographs of him when he played on the high school basketball team were still on the wall, as well as the one of him in his tux at the prom, and his trophy for winning the science contest remained atop the dresser, though it needed dusting. Just above it was his framed diploma from college. Lining the walls were other photos and holographs, from when he was still a baby until a month before he’d undergone what Julia always referred to as his Change. I could see his face twitching as he looked around at the memorabilia of his youth, and I felt like I could almost read his thoughts: They’ve turned the damned place into a shrine. Which I suppose we had – but to what he had been, not to what he was now. And I’d moved her in here because she was comforted by things from the past, even things she could no longer name.

“Hello, Jordan,” said Julia, smiling at me. “How are you?”

“I’m fine, Julia. Do you mind if I turn off the holo?”

“I was enjoying it,” she said. “How are you?”

I ordered the screen to deactivate.

“Is it August yet?” she asked.

“No, Julia,” I said patiently. “It’s February, just like it was yesterday.”

“Oh,” she said, frowning. “I thought it might be August.” Then a friendly smile. “How are you?”

Suddenly our son stepped forward. “Hello, Mother.”

She stared at him and smiled. “You are really quite beautiful.”

He reached out and took her hand with those incredibly long, stick-like fingers before I could stop him.

“I’ve missed you, Mother,” he said. He seemed like he was choked with emotion, but I couldn’t tell, because his voice never changed from those musical chimes. It was so unlike a human voice that I don’t know how we were able to understand him, but somehow we did.

“It is Halloween already?” asked Julia. “Are you dressed for a party?”

“No, Mother. This is the way I look.”

“Well, I think you’re beautiful.” She stopped and frowned. “Do I know you?”

He smiled, sadly I thought. “You did once. I am your son.”

She was silent for a moment, and I knew she was trying to remember. “I think I had a little boy once, but I can’t recall his name.”

“My name is Philip.”

“Phillip…Phillip…” she repeated. Finally she shook her head. “No, I think it was Jordan.”

“Jordan is your husband,” said Philip. “I’m your son.”

“I think I had a little boy once,” she said. Her face went blank for a moment. Then: “Is it Halloween already?”

“No,” he said gently. “I’ll let you go back to sleep. We’ll talk in the morning.”

“That will be fine,” she said. “Do I know you?”

“I’m your son,” he said.

“I’m sure I had a son a long time ago,” she said. “How are you?”

I could see a crystal tear run down his silver cheek. He tenderly laid her hand on the bed and stepped back. I activated the holoscreen, found a station that was still transmitting, killed the sound, and left her staring happily at it as I followed Phillip out into the hall, locking the door behind me.

We walked to the cluttered kitchen, with its ancient appliances and the three cracked tiles on the floor. (Each of us had been responsible for one of them.) I found the room homey and comforting, but I saw him looking at a burn spot on a counter that had been there since he’d accidentally made it as a kid and for just an instant I felt guilty about never having fixed it.

“You should have told me about her,” he said when he’d gotten his emotions under control.

“You shouldn’t have left, or become whatever it is that you are.”

“Damn it, she’s my mother!” The chimes were louder; I assumed he was yelling or snapping.

“There was nothing you could have done.” I ordered the refrigerator door to open and pulled out a beer. “You want one before you go back to wherever the hell you came from?” I thought about it and frowned. “Can you drink human drinks?”

He didn’t answer, but walked over and grabbed a beer. I could see that his mouth wouldn’t be able to accommodate the container, so I just watched and waited for him to ask for a glass, or maybe a bowl. He knew I was staring at him, but it didn’t seem to bother him. Instead something – not a tongue, and not a quite straw – slid out of his mouth, and when it was a few inches long he inserted it into the top of the container. He swallowed a few seconds later, and I knew he was somehow getting the beer into his mouth.

He set the container down and stared at an old pennant I had stuck on the wall when he was a little boy.

“You’re still a Pythons fan,” he observed.

“Always.”

“How are they doing?” There was a time when he actually cared, but that was many years ago.

“They haven’t had a decent quarterback since Christ was a corporal,” I answered.

“But you root for them anyway.”

“You don’t stop rooting for a team just because they’ve fallen on hard times.”

“A team, or a parent,” he said. I didn’t know how to reply to that, so I remained silent, and after a moment he spoke again. “I know there are medications for Alzheimer’s. I assume you’ve tried them?”

“There are all kinds of senile dementias. They call them all Alzheimer’s, but they aren’t. They haven’t yet found out how to cure the one she’s got.”

“There are specialists on other worlds. Maybe one of them could have done something.”

“You’re the space traveler,” I said bitterly. “Where were you when she might have been cured?”

He stared at me. I stared back, determined not to look away first.

“Why are you so angry at me? I know you cared for me once. I’ve never hurt you, I never took a penny from you once I got out of college, I never—”

“You deserted us,” I said. “You deserted your mother, you deserted me, you deserted your planet, you even deserted your species. That poor woman down the hall can’t remember the name of her son, but she can remember that people only look like you at Halloween.”

“It’s my job, damn it!”

“There are thousands of exobiologists right here on Earth!” I snapped. “I only know of one who turned into a silver-skinned monster with red eyes.”

“I was offered an opportunity that has been afforded very few men and women,” he replied. “I took it.” Even with the chimes he couldn’t keep the resentment out of his voice. “Most fathers would have been proud.”

I stared at him for a moment, amazed that he still didn’t understand. “I’m supposed to be proud that you became a thing that hasn’t got a trace of humanity left in him?” I said at last.

He stared right back through those multi-faceted insect eyes. “You really believe there is nothing human left of me?” he asked curiously.

“Look in a mirror,” I told him.

“Don’t I remember you telling me back when I was a boy that you should never judge a book by its cover?”

“That’s right.”

“Well?” he said.

“I just saw one of your pages slide out and suck up the beer.”

He signed deeply, to the delicate tinkling of chimes. “Would you have been happier if I couldn’t drink it?”

I seriously considered it for a minute. “No, that wouldn’t have made me happier,” I told him when I’d formulated my answer in terms even he could understand. “You know what would have made me happier? Grandchildren. A son who visited us for Christmas. A son I could leave the house to now that it’s finally paid off. I never asked you to follow in my footsteps, attend my college, go into my business, even live in this town. Would expecting you to want to be a normal human being be so goddamned wrong for a father?”

“No, it wouldn’t,” he admitted. Then: “For better or worse you’ve lived your life. I have the right to live mine.”

I shook my head. “Your life ended eleven years ago. You’re living some alien creature’s life now.”

He cocked his head to one side and studied me curiously. It seemed almost birdlike. “Which bothers you more – that I left Earth, or that I became what I am?”

“Six of one, a half dozen of the other. You knew you were the center of your mother’s life, but you left her and went to the far end of the galaxy.”

“Not quite the far end,” he said, and I couldn’t tell from the chimes whether that was sarcastic or sardonic or simply a straight answer. “And my mother wouldn’t have wanted me to stay here when I wanted to be out there.”

“You broke her heart!” I snapped.

“If I did, then I am truly sorry.”

“She spent years wondering why, back when she could still wonder,” I continued. “So did I. You had so much promise and so many opportunities, damn it! You could have been anything you wanted! The sky was the limit!”

“I became what I wanted,” he said gently. “And the stars were my limit.”

“Damn it, Philip!” I said, though I had promised myself never to call him by his human name. “You could have spent your whole life here and never seen a thousandth of the things Earth has to offer.”

“That’s true. But others have already seen them.” He paused, and turned his palms up in a very human gesture. “I wanted to see things no one else had ever seen.”

“I don’t know what’s up there,” I said, “but how different can it be? What makes our mountains and deserts and rivers so boring for you?”

He sighed, a delicate high-pitched tinkling sound. “I tried to explain that to you eleven years ago,” he answered at last. “You didn’t understand then. You don’t understand now.” He paused. “Maybe you just can’t.”

“Probably not,” I agreed. I walked to the cabinet with the missing knob, and opened the door with my fingernails the way I always do.

“You still haven’t replaced the knob,” he observed. “I remember the day I pulled it off. I expected to be punished. You just laughed, like I’d done something cute.”

“You should have seen the expression on your face when it came away in your hand, like you expected me to send you off to prison.” I felt a smile fighting to reach my mouth, and I pushed it back. “Anyway, it still opens.” I reached in, pulled down a couple of small bottles, and put them in my pocket.

“Mother’s medication?”

I nodded, holding them up. “She gets four different kinds in the morning, and two at night. I’ll give them to her a little later.” I pulled out another bottle.

“I thought you just said she only got two pills at night.”

“She does,” I said. I held up the third bottle. “These are sugar pills. I leave them on the dresser for her.”

“Sugar pills?” he repeated with what I assume passed for a puzzled frown.

“She thinks she can still medicate herself. She can’t, of course, but this gives her the illusion that she can. And if she takes six one day and forgets to take any the next, it doesn’t make any difference.”

“That’s very thoughtful of you.”

“I’ve loved her for close to half a century,” I answered. “I could have put her in a home and just visited her every day – or every tenth day. She probably wouldn’t know the difference. But I do this because I love her. Even if she doesn’t know it she has to be more comfortable in her own home, surrounded by the bits and pieces of her life. That’s why I moved her to your room instead of the guest room; the photos, the trophies, even that old catcher’s mitt in the closet, that’s all she has left of you.” I glared at him. “I didn’t walk out of her life for eleven years and come back only when she was past remembering me.”

He just looked at me but made no reply.

“Damn it!” I snapped. “Couldn’t you have said it was a secret mission for the military, even if it was a lie?”

“You’d have found out soon enough that I was lying.”

“I wouldn’t have tried to! We’d have been proud that you were serving your country, or your planet, or whatever the hell you were serving.”

“Is that it?” he demanded, suddenly angry. “You could lose a son to another world as long he didn’t enjoy it, as long as someone might be shooting at him?”

“That’s not what I said,” I replied defensively.

“That’s precisely what you said.” He stared at me with those insect eyes for a long minute. “You would never have understood. She might have, but you wouldn’t.”

“Then why did you never tell her?”

“I tried.”

“Well, you sure as hell didn’t succeed,” I said bitterly. “And it’s too late to try again.”

“She’s not the one who hates me,” he said. “I had already moved out and started my own life when this opportunity arose. You make it sound like I was your support network. I was an independent adult, living halfway across the country.” He paused. “I still don’t know which bothers you more: that I left the planet at all, or that I left it looking like this.”

“One day you were a member of our family. Four months later you weren’t even a member of the human race.”

“I still am,” he insisted.

“Look in a mirror.”

He placed a twelve-inch-long forefinger to his head. “It’s what’s in here that counts.”

“They say the eyes are the windows to the soul,” I replied. “Yours belong on an insect.”

“Just what the hell did you want from me?” he demanded. “Did you want me to go into business with you?”

“No, of course not.”

“Would you have disowned me if I’d been sterile and couldn’t give you any grandchildren?”

“Don’t be silly.”

“What if I’d moved halfway around the world? I might not have seen you more than once a decade if I had. Would you have disowned me as you did eleven years ago?”

“Nobody disowned you,” I pointed out, trying to keep my temper. “You disowned us.”

He sighed deeply. At least I think he did. With those chimes I couldn’t be sure.

“Did you ever think to ask me why?” he said at last.

“No.”

“If it bothered you that much, why didn’t you?”

“Because it was your choice.”

I think he frowned. I couldn’t tell for sure, not with that face. “I don’t understand.”

“If it was a necessity, something you had to do to save your life or something like that, I’d have asked. But since it was a freely-made choice, no, I didn’t care why you did it, only that you did it.”

He looked long and hard at me. “All those years that I lived here, and even after I left, I thought you loved for me.”

“I loved Philip,” I said, and then grimaced. “I don’t know you.”

Suddenly I heard Julia knocking weakly at her door, and walked down the shopworn hallway to unlock it. I hadn’t noticed how threadbare the carpet had become, or the crack in the plaster, but I saw him looking at it so I looked too, and made up my mind to do something about it one of these days.

I uttered the code word, softly enough that she couldn’t hear it on her side of the door, and a moment later it swung open. She was standing there barefoot in her nightgown, thin and frail, her arms and legs like toothpicks with withered flesh on them, looking mildly puzzled.

“What’s the matter?” I asked.

“I thought I heard you arguing with someone.” Her gaze fell on Philip. “Hello,” she said. “Have we met before?”

He took her hand very gently and gave her what seemed like a wistful smile, though I couldn’t be sure. “A long time ago.”

“My name is Julia.” She extended a wrinkled, liver-spotted hand.

“And mine is Philip.”

A frown crossed her once-beautiful face. “I think I knew someone called Philip once.” She paused, then smiled. “That’s a very pretty costume you’re wearing.”

“Thank you.”

“And I love your voice,” she continued. “It sounds like the wind chimes on our porch when a summer breeze blows through them.”

“I’m glad it pleases you,” said the creature that used to be our son.

“Can you sing?”

He shrugged, and his whole body seemed to sparkle as the light reflected off it. “I really don’t know,” he admitted. “I’ve never tried.”

“You look hungry,” she said. “Can I make you something to eat?”

I prodded him and when he looked at me, I very briefly shook my head No. She’d already set the kitchen on fire twice before I started ordering all our meals delivered.

He picked up on it instantly. “No, thank you. I ate just before I arrived.”

“That’s too bad,” she said. “I’m a good cook.”

“I’ll bet you make a wonderful Denver pudding.” That had always been his favorite dessert.

“The best,” she answered, glowing with pride. “I like you, young man.” Then a puzzled frown. “You are a man, aren’t you?”

“Yes, I am.”

“Is it Halloween?”

“Not yet.”

“Why are you wearing that costume, then?”

“Would you really like to know about it?”

“Very much,” she said. Suddenly she shivered. “But it’s chilly standing here barefoot in the doorway. Would you mind very much if I got under the covers while we chatted? You can sit right next to the bed, and we can be nice and cozy. Jordan, could you make me some hot chocolate? And maybe some for… I’ve forgotten your name.”

“Philip,” he said.

“Philip,” she repeated, frowning. “Philip. I’m sure I knew a Philip once, a long time ago.”

“I’m sure you did too,” he said softly.

“Well, come along.” Julia turned, walked back into her room, and climbed into the bed that had once belonged to Philip, propping herself up with some pillows and pulling the blanket and comforter up to her armpits. He followed her and stood next to the bed. “There’s no need to stand, young man,” she told him. “Pull up a chair.”

“Thank you,” he said, getting the chair he’d used while writing his masters’ thesis on his computer and carrying it over so that he was sitting right next to her.

“Jordan, I think we’d like some hot chocolate.”

“I don’t know if he drinks it,” I replied.

“I’d very much like some,” he said.

“Good!” said Julia. “You can bring two cups on a tray, one for me and one for…Excuse me, but I don’t know your name.”

“It’s Philip.”

“And you must call me Julia.”

“Why don’t I just call you Mother?” he suggested.

She frowned in puzzlement. “Why would you do that?”

He reached out and very gently held her hand. “No reason, Julia.”

“Jordan,” she said, “I think I’d like some hot chocolate.” She turned to Philip. “Would you like some too, young man? You are a man, aren’t you?”

“I am, and I would.”

I left to get the hot chocolate before she asked again. I went out to the kitchen, mixed up a fair-sized pan – I don’t know why; there were only two of them, and I don’t drink the stuff myself – and was about to pour a pair of cups. Then I remembered the shape of his hands and fingers, and decided he was less likely to spill a mug, so I got the old chipped Pythons mug he’d given me for my birthday when he was nine or ten years old. I think he’d saved up a month’s allowance to buy it. I looked at it fondly for a moment, and wondered if he’d recognize it. Then I remembered who – or rather what – I was pouring it for, and got on with it. The whole process took maybe three or four minutes, start to finish. I put the cup and the mug on a tray, added a spoon for Julia since she liked to stir everything whether it needed it or not, and folded a pair of napkins. Then I picked up the tray and carried it back to the bedroom.

“Just put it on the table, please, Jordan,” she said, and I placed it on her nightstand.

She turned back eagerly to Philip. “What were they like?”

To this day I don’t know how a face like his could look wistful, but it did. “They are the most beautiful things I’ve ever seen,” he said, his voice chiming delicately. “I want to say they’re transparent, but that’s not exactly right. Their bodies are actually prisms, separating the rays of the sun and casting a hundred colors on the ground beneath them as they fly.”

“They sound wonderful!” said Julia, her face more alive than I’d seen it in months.

“They swarm by the tens of thousands. It’s as if a miles-long kaleidoscope has taken wing, and the ever-changing colors cover an area the size of a small city.”

“How fascinating!” she said enthusiastically. “What do they eat?”

A shrug. “No one knows.”

“No one?”

“There are only about forty men and women on the planet, and none of us has yet climbed the crystal mountains where they nest.”

“Crystal mountains!” she repeated. “What a pretty picture!”

“It’s not a world like any you have ever imagined, Julia,” he said. “There are plants and animals no one’s ever even dreamed of.”

“Plants?” she asked. “How different can a plant be?”

“I saw some potted plants in your living room, right by that old piano that’s probably still out of tune,” he said. “Do you ever talk to them?”

“Of course,” said Julia. She flashed him a smile. “But they never answer.”

He returned her smile. “Mine do.”

She clutched his hand with both of hers, as if she was afraid he might leave before telling her about his plants.

“What do they say?” she asked. “I’ll bet they talk about the weather.”

He shook his head. “Mostly they talk about mathematics, and once in a while about philosophy.”

“I knew about those things once,” she said, and then added hazily: “I think.”

“They have no sense of self-preservation, so they’re not concerned with rain or fertilizer,” continued Philip. “They don’t care if they’re eaten or not. They use their intelligence to solve abstract problems, because to them all problems are abstract.”

I couldn’t help but speak up. “They really exist?”

“They really exist.”

“What do they look like?”

“Not like any plant on Earth. Most of them have translucent flowers, and almost all of them have rigid protrusions, like, I don’t know, tiny branches that rub together. That’s how they communicate.”

“So you speak in chimes and they speak in little clicks?” asked Julia. “How do you understand each other?”

“The first few men to study them spent half a century learning the meanings behind their clicking and rubbing. Now we both speak to my computer, and it translates each of our languages into the other’s.”

“What do you say to a plant?” I asked.

“Not much,” he admitted. “They’re very different. But after you speak to them for any length of time, you know why Men fight so hard to stay alive. Nothing matters to them. They accomplish nothing and they care about nothing, not even their mathematics. They have no hopes, no dreams, and no goals.” He paused. “But they are unique.”

“I’d—” I began, and then stopped. I’d been about to say I’d like to see one of those plants, but I didn’t want him to think he’d said anything of interest to me.

Just then Julia reached for her cup, but either her vision wasn’t working right or her hand was shaking – they both fail a lot these days, her eyes and her hands – and it began tottering, about the spill over. Philip moved his fingers so fast my eyes couldn’t follow it, and he righted the cup before three drops had fallen to the tray.

“Thank you, young man,” she said.

“You’re welcome.” He glanced at me, and his expression said: Whatever you think of what I’ve become, that’s something I couldn’t have done twelve years ago,

There was a momentary silence. Then Julia spoke up again. “Is it Halloween?”

“Not for a while yet.”

“Oh, that’s right! You wore your costume on some other world. Tell me more about the animals.”

“Some of them are beautiful, some of them are huge and awesome, some are petite and delicate, and all of them are different from anything you’ve ever seen or even imagined.”

“Do they have…?” she frowned. “I can’t remember the word.”

“Take your time,” he said, holding her hand in one of his and patting it gently with the other to comfort her. “I’ve got all night.”

“I can’t remember,” she said, close to tears. Her whole body tensed as she reached for a word that might forever elude her. “Big,” she said at last. “It was big.”

“A big word?” he asked.

“No,” she said, shaking her head. “Big!”

He looked puzzled. “Do you mean dinosaurs?”

“Yes!” she shouted, an expression of relief on her face as the missing word finally appeared.

“We don’t have dinosaurs,” he said. “They’re unique to Earth. But we have animals that are bigger than the biggest dinosaur that ever lived. One of them is so big, so huge, that he has no natural predators – and because nothing can hurt him, and he has no reason to hide, he glows in the dark.”

“All night long?” she asked with a giggle. “Can’t he turn off the glow so he can sleep?”

“He doesn’t have to,” said Philip as if speaking to a child, which in a way she was. “Since he’s glowed all his life it doesn’t bother him or keep him awake.”

“What color is he?” asked Julia.

“When he’s hungry, he glows a deep red. When he’s angry, he’s blue.” Finally he smiled. “And when he wants to attract a ladyfriend, he becomes the brightest yellow you ever saw, and pulsates like crazy, almost like a 50-foot-high flashbulb going off every other second.”

“Oh, I wish I could see him!” said Julia. “It must be a wonderful place, this world you live on!”

“I think so.” He looked over at me. “Not everybody does.”

“I would give everything I have to go there.”

“It doesn’t take quite everything,” said Philip, and I tried to imagine the tone of voice he’d have used if he had still been human. “Just most things.”

She stared at him curiously. “Were you born there?”

“No, Julia, I wasn’t,” he said and somehow his face seemed to reflect an infinite sadness as he used her proper name. “I was born right here, in this house.”

“It must have been before we moved here,” she said, dismissing the notion with a shrug of her narrow shoulders. “But if you were born here, why are you wearing a Halloween costume?”

“This is what people look like where I live.”

“It must be one of the suburbs,” she said with conviction. “I don’t remember seeing anyone like you at the supermarket or the doctor’s.”

“It’s a very distant suburb,” he said.

“I thought so,” said Julia. “And your name is…?”

“Philip,” he said, and for the second time that night I saw a shining tear roll down his cheek.

“Philip,” she repeated. “Philip. That’s a very nice name.”

“I’m glad you like it.”

“I’m sure I knew a Philip once.” Suddenly she yawned. “I’m getting a little tired.”

“Would you like me to leave?” he asked solicitously.

“Could I ask you a favor?”

“Anything.”

“My father used to tell me a bedtime story when I went to sleep,” said Julia. “Would you tell me a fairy tale?”

“You’ve never asked me for one,” I blurted out.

“You don’t know any,” she replied.

I had to admit she was right.

“I’ll be happy to,” said Philip. “Shall we lower the light a little – just in case you fall asleep?”

She nodded, spread her pillows out, and lay her head back on one of them.

He reached for the lamp in the wall above the nightstand – the only thing I’d added to the room since he’d left. When he couldn’t find a switch, he remembered that it worked by voice command and ordered it to dim itself. Then, in the same room where she had told him a fairy tale almost every night, he told one to her.

“Once there was a young man,” he began.

“No,” said Julia. He stopped and looked at her curiously. “If this is a fairy tale, he has to be a prince.”

“You’re right, of course. Once there was a prince.”

She nodded her approval. “That’s better.” Then: “What was his name?”

“What do you think his name was?”

“Prince Philip,” said Julia.

“You’re absolutely right,” he replied. “Once there was a prince named Philip. He was a very well-behaved young man, and tried always to do the bidding of the King and Queen. He studied chivalry and jousting and any number of princely things – but when his classes were done and his weapons were polished and put away and he’d finished his dinner, he would go to his room and read about fabulous places like Oz and Wonderland. He knew that such places couldn’t exist, but he wished they could, and every time he found a book or a holo about a new one he would read it or watch it, and wish that somehow, someday he could visit such places.”

“I know just how he felt!” said Julia with a happy smile on the wrinkled face that I still loved. “Wouldn’t it be wonderful to walk along the yellow brick road with the Scarecrow and the Tin Man, or to have a conversation with the Cheshire Cat, or visit the Walrus and the Carpenter?”

“That’s what Prince Philip thought too,” he agreed. He leaned forward dramatically. “And then one day he made a wonderful discovery.”

She sat up and clapped her hands together in her excitement. “He learned how to get to Oz!”

“Not Oz, but an even more wonderful place.”

She leaned back, suddenly tired from her efforts. “I’m very glad! Is that the end?”

He shook his head. “No, it isn’t. Because you see, nobody in this place looked like the Prince or his parents. He couldn’t understand the people who lived there and they couldn’t understand him. And they were afraid of anyone who looked and sounded different.”

“Most people are,” she said sleepily, her eyes closed. “Did he wear a Halloween costume too?”

“Yes,” said Philip. “But it was a very special costume.”

“Oh?” she said, opening her eyes again. “How?”

“Once he put it on, he could never take it off again,” explained Philip.

“A magic costume!” she exclaimed.

“Yes, but it meant that he could never be the King of his parents’ country, and his father the King was very, very angry at him. But he knew he would never have another chance to visit such a wondrous kingdom again, so he donned the costume and he left his palace and went to live in the magical kingdom.”

“Was the costume uncomfortable to put on?” she asked, her voice very briefly more alert than it had been.

“Very,” he answered, which was something I’d never thought about before. “But he never complained because he never doubted that it was worth it. And he went to this mystical land, and he saw a thousand strange and beautiful things. Every day there was a new wonder, every night a new vision.”

“And he lived happily ever after?” asked Julia.

“So far.”

“And did he marry a beautiful princess?”

“Not yet,” said Philip. “But he has hopes.”

“I think that’s a beautiful fairy tale,” she said.

“Thank you, Julia.”

“You can call me Mother,” she said, her voice sharp and cogent. “You were right to go.” She turned to me, and somehow I could tell it was the old Julia, the real Julia, looking at me. “And you had better make your peace with our son.”

And as quickly as she said it, the old Julia vanished as she did so often these days, and she was once again the Julia I’d grown used to for the past year. She lay back on the pillow, and looked at our son once more.

“I’ve forgotten your name,” she said apologetically.

“Philip.”

“Philip,” she repeated. “What a nice name.” A pause. “Is it Halloween?”

Before he could answer she was asleep. He leaned over and kissed her on the cheek with his misshapen lips, then stood up and walked to the door.

“I’ll leave now,” he said as I followed him out of her room.

“Not yet,” I said.

He stared at me expectantly.

“Come on into the kitchen,” I said.

He followed me down the shabby hallway, and when we got there I pulled out a couple of beers, popped them open, and poured two glasses.

“Did it hurt that much?” I asked.

He shrugged. “It’s over and done with.”

“There really are crystal mountains?”

He nodded.

“And flowers that talk?”

“Yes.”

“Come into the living room with me,” I said, heading out of the kitchen. When we got there I sat in an easy chair and gestured for him to sit down on the sofa.

“What is this about?” he asked.

“Was it really that special?” I asked. “That much of an honor?”

“There were more than six thousand candidates for the position,” he said. “I beat them all.”

“It must have cost them a pretty penny to make you what you are.”

“More than you can imagine.”

I took a sip of my beer. “Let’s talk.”

“We’ve talked about Mother,” he replied. “All that’s left is the Pythons, and I haven’t kept up with them.”

“There’s more.”

“Oh?”

“Tell me about Wonderland,” I said.

He stayed for three days, slept in the long-unused guest room, and then he had to go back. He invited me to come visit him, and I promised I would. But of course I can’t leave Julia, and by the time she’s gone I’ll probably be a little too old and a little too infirm, and it’s a long, grueling, expensive trip.

But it’s comforting to know that if I ever do find a way to get there, I’ll be greeted by a loving son who can show his old man around the place and point out all the sights to him.

About the Author

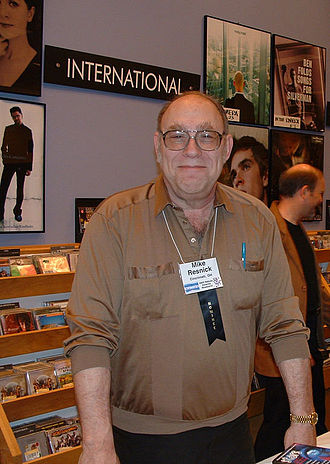

Mike Resnick

Mike Resnick is an American science fiction writer and was executive editor of Jim Baen’s Universe. Resnick’s style is known for the inclusion of humor; he has probably sold more humorous stories than any science fiction author except Robert Sheckley, and even his most grim and serious stories have frequent unexpected bursts of humor in them. Resnick enjoys collaborating, especially on short stories.

About the Narrator

Patrick Bazile

Patrick is an American Actor/Voice Over Talent born and raised in Chicago, Illinois. Patrick has voiced everything from PSAs to major product brands, with a deep, commanding voice often referred to as “The Voice of God.”