Escape Pod 893: A Series of Endings

A Series of Endings

by Amal Singh

This is the story of Roopchand Rathore, time traveler, fighter, poet, cancer-survivor, inventor. While his story has many endings, there’s only one true beginning, and it takes place in the humid but pristine backwaters of sun-drenched Kerala.

A scene from a movie, but a true-to-roots, hand on heart, scene of value, scene of promise, scene of a birth. A child’s cry from inside a thatched hut. Outside the hut, a muddy trail that disappears amid a canopy of palm trees. A silent rush of water from a nearby canal. A rickety boat tied to the thick stem of a drooping coconut tree that looks like a sullen traveler whose hair is in disarray.

The child is born to parents who aren’t true Keralites by birth, but by heart. His face is like the moon. His mother insists on naming him Chandru, but his father calls him Roop. By consensus, he is named Roopchand.

“He will be a painter like his grandfather,” says Roopchand’s father, Karamchand, upon seeing his eyes, bright and black and full of promise. Roopchand coos at this, clutching his father’s pudgy finger. His father mumbles a song’s mukhda under his breath but is rudely interrupted by the mother, Poornakala.

“No,” says Poornakala. “He will be a healer.” Roopchand lets out a wail at this, making his dissatisfaction known.

“Maybe, one day, he will become a boat racer like his father.” Roopchand’s wail turns into a steady baby hum. He will be none of those things his parents just spoke about.

This is his one true beginning.

Roopchand Rathore hurtles toward Europa. Inside the BreathPod, disconnected from the Marionette-V ship, Jupiter-bound, but wrecked after crossing Mars, the only thing to keep him company is the constant drone of his pod’s AI unit, whose two tasks are reminding him of his rapidly depleting oxygen, and reciting him poems. Its Urdu is heavily accented, but workable. RR can’t complain. The vastness of space is its own poetry.

“Hazaaron khwaishein aisi ki har khwaish pe dum nikle.” says the AI, in a broken, un-Ghalib like manner. This is RR’s ending. An ending of a life lived in the service of science, but a life incomplete yet. As the globe of Europa approaches him, he dreams about its silicate surface, hiding a deep, icy ocean of water, and an invertebrate lifeform he had termed as jal-jaadugar. Water magicians. The probe he’d sent had disappeared beneath the crust following a storm and an earthquake, but still managed to send and receive signals. The probe couldn’t have survived the intense pressure of the icy waters, yet, miraculously, the signal coming back was a series of clicks, a response.

It was a miracle. Almost like magic. From a jaadugar inside water.

But we’re not concerned about the hows and the whys of his discovery. The discovery happened, that’s the point. And despite the discovery, despite the near-miss launches, and a final success, and Marionette-V’s course across space, his mission was not on its way to Europa, but on its way to failure.

But death is not a failure. Death is certain, failure is not. Death is an ending, failure is not.

“Rumi,” said Roopchand Rathore, closing his eyes. “Recite Rumi to me.”

“Your oxygen is close to ten percent, and all my facilities are spent in keeping this pod operational. Searching for Rumi would deplete it faster . . . ” the AI’s voice breaks off. Close to failure.

Fifteen minutes later, an ending comes.

When Roop goes to the beginning, he finds himself gathering consciousness near the coconut tree and the boat. Not at the moment of his birth, but at an uncertain point, because all early life is an uncertain haze, a miasma of memories cobbled together. It always happens like this for him, after an ending.

One never truly remembers their birth, or their first birthday, the first time they got sick. There’s always a cloud. That’s why beginnings are overrated.

He is tugging the boat, his fists clenched, as a coconut falls from above and neatly breaks into two as it hits the ground in front of Roop. His heart leaps in terror of an almost-death, then sinks at seeing the coconut water and muddying the ground, making it mulch.

He remembers he needs to be at a boat race, cheering his babuji. Screaming babuji amidst screams of achan and anna seems odd to him, but he gathers courage to do so. And he runs toward the narrow main road where blue scooters speed like spaceships, driven by lungi-clad men with cigarettes dangling from their blackened lips. The road snakes toward the site of the race. Roop runs after a scooter. The rider stops the scooter and gestures to Roop to hop along, which he happily does.

“Are you also going to watch the race?” Roopchand asks the driver.

“No, I loathe boat races. They’re for adrenaline junkies. I’m a man of letters.”

To Roopchand, the answer doesn’t make a lot of sense. He is young, still, and doesn’t understand why someone would hate boat races.

“My father is racing,” says Roopchand. “He’s going to win.”

“How are you sure?”

“He always wins.” RR speaks, but his voice gets lost in the rush of the hot, wet, afternoon air. He tries to speak a bit louder, to make the driver know that he is the son of a boating champion, but the wind doesn’t relent. With the wind comes the intoxicating, spicy-charred-sweet smell of pothu roast. His stomach rumbles like thunder, but pothu—beef—is sacrilege for Roop. Would it still hurt to have a taste? God won’t be angry at him for yielding to this temptation? After all, there are gods here as well. The gods who like people who eat pothu. What’s the difference?

But there is also the matter of the race.

The man stops his scooter near a stall that sells beef roast and parotta. RR doesn’t rebel. At that moment, the race is a distant possibility in his mind. Whether his father, Karamchand, wins it or not doesn’t concern him. What concerns him is the taste of a forbidden animal. Looking at the charred brown chunks dripping with oil, swimming in a coconut onion gravy with snippings of curry leaves sprinkled on them, RR couldn’t imagine that the chunks would have once belonged to a full-grown beast. He can’t tell which part those brown bits came from.

“Two plates.” RR hears the voice of the man. In this miasmic moment, where the world ceases to exist at the corners of his eyes, he is handed a plate full of forbidden food. RR tears off the parotta like he would a roti and picks up a healthy chunk of the roast beef like he would do with a cube of paneer. He takes a bite.

RR would have said, later in his life, that tasting the beef was the closest he had felt, ever, to being in the presence of divinity. But then the man had taken the shape of the death-god his father had told him stories of, with horns on his head, and fiery eyes.

Roopchand opens his eyes again, near the coconut tree, and the boat, intimately aware of his previous end, at the bloody hands of a stranger he had met on the roads. This time around he goes straight to the race and reminds himself not to give in to temptations of a certain food.

But he reaches the site of the boat race too late, still. Two boats cruise toward the finish with gusto, and his father is in neither of them. He finds his champion father painfully slicing the waters, his tired eyes searching for the finish line, somewhere far behind, maybe the tenth, maybe the eleventh. At the moment, RR forgets all counting as he watches the disappointed, sorry figure of his father.

Roopchand Rathore is drinking aversan with Xlarin-Midan-Wa, a blue-veined, Ganymedian, whose body absorbs all sounds and all light. In that moment, Roopchand is sitting in the darkness of a cave, taking warmth from the generosity of the aliens who found his pod rammed into ice, surrounded by the vapory entrails of chemicals. With memories cobbled together from nested memories, hazy events, calculations, quotes, languages, and wisdoms of lifetimes spent earlier, RR managed to helm Marionette-V again and again, sped toward Europa, but this time missed it, and landed in Ganymede instead, finding his jal-jadoogar. Had Xlarin-Midan-wa not come up to the surface for xir biweekly trip, xe would not have found Roopchand. And yet again, this would have been a fruitless ending. But now Roopchand sits inside the cave, reciting a nazm to an alien whom he only knows as jaadugar.

“Hazaaron khwahishein aaisi ki har khwahish pe dam nikle . . . ” says Roopchand. The nazm reaches the Ganymedian through the thin air, an air unsuited for Roopchand’s survival. Xlarin-Midan-Wa stays silent for the next two minutes, and then he speaks. His voice is all clicks and high-pitched notes, inaudible to Roopchand.

“You keep repeating that phrase.” the Ganymedian says. The sounds make a shape in Roopchand’s brain. A shape that screams condescension. Apathy. The jal-jadoogar don’t like him at all.

“I have lived a lot of lives and at least four of them were dedicated to finding Ganymedians.”

“We only live one life and all of that goes into finding a way to live forever.”

RR laughs. His body rattles like the wet sack of bones it is. Then he stops, fearing his laughter will take his life away. That a final hitch would snatch his soul from somewhere deep inside him and transfer it back across the multifolds of space and time and drop him inside the body of a teenager, clutching a frayed rope, waiting for his father to come back from a race.

“Take it from me. Living forever is not the joyride you think it is.”

“Will you tell it to my brethren? These exact words. Not one blemish. Because I have been trying to convince them, and they reject my words each time. Perhaps if the same words come from a different being, they might see reason.”

The jal-jadoogar’s words are a razor slice to RR’s brain. Even if they’re a request, the Ganymedian’s language takes an ugly shape inside RR, and it takes him a long time to form a cohesive thought from those clicks. The end result is a low din, then an absence of sound, like just after a blast. In that absence, RR understands that he has to meet other Ganymedians.

Cloaked in a brown rag, carrying a bone white staff that emits a sapphire glow from its tip, RR walks inside a domed vault. A cavernous space, where the sound of his footsteps ricochet off the walls and come back to him amplified, the vault is not a traditional space that houses riches like gold and silver. It is instead a space that reminds RR of a church he had been inside, in a previous life, a previous beginning. The walls of the vault have tubes attached to it, and through the tubes RR can make out letters wafting upward, coiled in a cloudy embrace. Yes, letters, runes, images, signs, all swirling inside glass tubes moving upward, where they meet further tubes, crisscrossed, which lead to a glowing apparatus near the back of the vault.

RR walks toward the center of the room where, behind a large mahogany desk, crouches a creature half-horse, half-bat, reading an ancient book. The leathery cover with gleaming scales like crocodile hide seems to groan with each turn of the page, as if denying to impart its various secrets to the reader. RR clears his throat. The creature looks up and flaps its black, shadowy wings. It smiles and shows its entirely too-white horse teeth.

“I’m here to return this,” says RR, pointing to his staff.

“Place it on the table,” says the creature. “Has the staff completed its final duel?”

“Slayed the demon of Varhansa, yes.”

“Your text will be with you any moment now. I request you to be patient.”

RR stands straight, clutching the frayed edges of his cloak, feeling its rough fabric on his calloused palms. The creature uses its bat claws to turn the page of the ancient text, and grunts in amusement at a line. An inordinately long moment passes. Groans of words all around, swiveling in pipes, poetry in vapor. RR scratches his chin and admires the domed ceiling above.

“What sort of answers do you seek from the text?” the creature says finally, without looking up.

“Whatever the text gives me, I’ll take that as an answer.”

“Even if it’s meaningless?”

“I have lived many lives, lives vastly different from the one I am living now, and I have learned that there’s no meaning to anything in this world.”

“Why wait for the text so patiently, then?”

“Curiosity.”

The creature shrugs as only it can, waves appearing on its wings, its horsehead freckling. Then, it closes the book it’s reading, reaching for something in the air above. RR’s eyes follow its movements, and it’s only here he notices an opening of a brass tube six feet above the creature. To the ordinary eye, the tube would seem fit for ventilation, but not in this place. Smoke curls in a halo at the circular opening and forms concentric rings. The creature picks the rings one by one, and they solidify in its grip, fusing into each other, becoming one thick crown, emblazoned with glowing letters. RR takes the crown and brings it closer to his eyes.

“What does it say?”

“My text is meant only for me,” says RR. “Thank you for your service.”

The creature goes back to reading its book as RR turns around on his feet and walks out of the vault.

Outside, it’s an eternal winter. Dead things covered in age-old frost in corniches of trees find another frost blanket. RR’s boots crunch against hard snow as he walks toward the edge of the forest. He can’t feel his fingers, but the crown that holds his answers grows colder at every step. Snowflakes form a white crust on the engravings, which RR painstakingly removes to read as he walks. His fingertips have gone from pink to violet in a span of minutes, but he persists. He blinks away snow from his eyes to read his text. It’s an old language, older than time, but he knows all languages, even the ones not discovered yet in this time.

He reads the words, but his mind is elsewhere.

He is standing at the tip of a volcano holding the staff, as the magma roils into a monster-shape. Flame hands, flame torso, a red-jewel heart, and eyes two suns. But RR stands unfazed, gripping the staff, remembering the promise of Guru Raj. “Kill the demon and get your answers.” Guru Raj had spoken those words in his mind when RR had brought to him ten containers of milk, balancing them on his head, ascending the Ten Thousand Steps. And as RR stands at the fiery precipice, he remembers the steps he had climbed to his teacher. And he knows in his heart that slaying the monster would be easier than balancing the teetering ceramic milk pots on his head.

The demon of Varhansa comes down upon him as RR plunges the staff deep into its amber heart. It goes in smoothly, like a hot knife through butter. The demon of Varhansa bursts into more flames and the volcano mellows down. RR slides down the slope and finds himself at the base of a mostly quiet but grumbling mountain as ash rains from the sky.

His mind comes back from the fiery surroundings to frigid ones. His eyes refocus on the words.

The forest trails away into a white, smoky nothingness. RR sits down on the hard, cold ground, taking in the words written for him by an invisible hand.

What you seek waits for you at the beginning.

RR closes his eyes as the cold kisses him farewell.

The jal-jadoogar all look the same but speak in different clicks. RR knows what he has to say to them. They look at him expectantly, as if he will deliver to them a sermon. At this moment, RR is a prophet. Ruined face, battered body, gasping for air on an alien planet, on the mercy of a Ganymedian device that allows him to breathe and survive underwater.

RR floats, but the Ganymedians stand. Their bodies are misshapen blobs held together by a string, a six feet-long umbilical cord running at the edge. Their features are a science diagram of their own, part double helical structure, part isopropyl cyanide, but a complete chemical oddity. And inside water they take a dreamlike shape that the harsh exterior of the moon would stretch and morph into a different shape.

In clicks, the Xlarin-Midan-Wa introduces RR. In clicks, he receives a response. Their bodies rush toward him like an Olympian racer’s last dash to the finish line and stop inches away from his face, the watery everything around him threatening to become a fleshy grave where his innards would swim for eons like flailing tentacles.

“Your arrival was written in the depths, which have since been washed.”

“We will soak up your knowledge and swim to the surface. We’ll haunt this icy land with our newfound independence.”

“Tell us, tell us, tell us.”

“I’ll tell you a story first,” RR says. The clicks stop, and the only sound around RR is the sound of a cold, empty sea.

“Where I come from there was once a sage who prayed atop a mountain to a god who would grant him any wish. The sage wanted to be immortal. So, he prayed for a thousand years, and when he opened his eyes, the world was awash in fire. Then, he prayed for a thousand more, and when he opened his eyes, the world was in autumn, old, and withering. After the third millennia, when the land was green and baby new, the god came to him in the form of a young girl climbing the mountain. The girl told the sage that she was ready to be given the gift of immortality now that she had climbed the mountain. The sage was befuddled, as it was the first thing he had done three thousand years ago. The girl took his hand and told him, ‘Look around you. The world has changed a thousand times over, and you are still the same. Do you still think you didn’t get the boon the first day itself? When you began it all?’” Rage consumed him as he fell to his knees, and he cursed himself for being blind to the world around himself. But soon the rage was replaced by anguish and helplessness.

“What did the sage do?”

“The sage wept at the feet of the girl. Then he climbed down the mountain and lived the rest of his days in anonymity, meeting people of lands far off, building civilizations, and fighting in wars. But he was never at peace. Some say he’s still around, searching for some kind of an answer.”

“Are you the sage?”

“No, I am the little girl who has come here to tell you. You have lived long and fruitful lives already, and there’s nothing beyond all this.”

“You’re no god.”

There’s silence again. The water shivers around RR. But soon, after a cruel click, and a puncturing sound, a redness swells.

RR grabs the coconut mid-fall and smashes it on the tree-stem. He drinks the water and scoops up the cream collected at the white base. His ears catch the melodious clang of a payal. The rhythm only belongs to one woman. RR turns and looks at the face of his mother, all hard lines, yet radiating a peculiar youth with her eyes. She has brought him a plate of samosas. RR remembers from the many lives he has lived that he loves this nutty, warm smell of fried dough enveloping mashed, spicy potatoes. It all gushes back, once again, as it has, many times before. For a moment, he loses everything. Then he steadies himself, holding the stem of the tree and the gaze of his mother.

“Today, you have to win.”

“You mean father will win. I’ll cheer for him from the sides. Where’s he?”

“No, I mean literally. You are taking his place. It has already been arranged.” RR catches a glint of the afternoon sun in the gem of his mother’s bindi.

“What? But why . . . ? I don’t even know how.”

“It’s in your blood. You’ll know when you hold the oar.”

And like the crescendo of music he had often heard in the movies he had watched growing up, he somehow hears a chorus of birds, shrill sounds of insects, more clang of payals, and a jaltarang, all coalescing into a moving melody, nudging him toward the canal where the boat race was going to be held.

“Will you come with me?” he asks his mother.

“I’ll cheer you on from here. I’ll pray for you. And so will your father.”

RR smiles and rushes inside his hut, where his father sits on a stool, massaging oil on his elbow, where there is a sharp red gash. The old man looks up and locks gazes with RR. Then, with a labored movement, he hands him a wooden oar.

“This has seen many races, son. Treat it like it’s an extension of your hand.”

And in RR’s mind, from another time, similar words echo, of a bearded man, who had handed him a staff, and said, “The staff is your hand, and your hand slays the beast.” He touches his father’s feet, like he touched his Guru’s feet, and takes the oar.

When he leaves his hut and takes the beaten trail to the road, he forgets the ending he met in one of his lives following the same path. His head thrums with all the endings he has met, but he remembers not his one true beginning, which, he’s sure, involves his mother, his father, that hut, and that tree he left behind.

He reaches the backwaters. The air is humid, and his shirt sticks to his chest, pools of sweat forming on it like so many Rorschach tests. Palm trees form a canopy over a narrow river body, which widens later. Sixteen snake boats with paddlers ready to race. RR looks at his oar and the long boat and the gap among the sixteen men where his father used to sit. He is not special, just one of many. A child even, while the rest are muscular and lean. Sweat glistens on their chests proudly.

But RR has his father’s oar, and he remembers how to slay beasts. He joins the group, saying nothing. They look at him, suspiciously, expecting his father.

“I am all you get today,” he says. A dark, clean-shaven man spits on the muddy ground.

“Great, we’ll lose this year.”

RR catches the fallen gazes of his teammates. Soon, their eyes take a cruel turn, and he sees not kindness but venom in them. He is painfully reminded of a cold evening in water surrounded by aliens who demanded answers from him. RR grips his oar tightly.

“Do you believe in magic?” he says to his teammates, desperately. “This oar is infused with it. And today, we will win.”

“Even a magic oar has to be expertly handled, and you’re not your father,” says another man. His name is Sundaran. He has a mole on his left cheek, and a scar on the other. RR has an urge to slap him, but he knows he’ll end up with broken bones and a broken soul if he does something like that.

“Let’s do it and hope for the best,” says another man, whose voice is gentle, but the manner stern. He looks senior. There’s a consensus. The men wait for the gunshot.

They wait, and wait, but the sound defies expectation. It comes, as sudden as a stroke, and all the sinewy hands are plunged into motion. RR grips his oar firmly and mimics the paddlers. Slowly and steadily, his blood obliges, and the oar does his bidding, like the staff did, in another age, in another time. The man with the mole grins at RR as sweat trickles down his brow. There’s only one boat ahead of them, and at least three men on the boat look battle-strained.

RR gives it everything he has. So do his teammates. And just before the finish line, their snake boat’s head slithers ahead of the other. A roar of his teammates deafens him, momentarily, but inadvertently. He smiles. Moments later, as his teammates hurl his lithe, small teenage body high up in the air in celebration of their win, RR forgets all his previous endings. This is his one moment, one life, one beginning.

“Take it,” says the man with the mole, handing him the glittering trophy. “Take it to Karamchand. Make sure he holds it properly. Make sure he sings to it.”

Roopchand grabs the trophy, shakes hands with his teammates, and runs toward his home, taking the sun-beaten road. His heart leaps in joy at the full life ahead of him, his mind holding the memory of only one life lived. As he takes a turn in the road, a smell wafts to his nose. A smell of something divine. His ears catch a rat-a-tat of an old scooter, groaning along the road surrounded by palm trees. Roopchand’s legs feel weary all of a sudden as he looks at the man who is riding the scooter. He applies the brakes and looks at RR curiously.

“Won the race, I see,” he says. “Aren’t you hungry? After all that relentless paddling?”

RR’s stomach grumbles as the smell of a beast roasting grows profound. The man seems kind. “I am,” says RR, after much trepidation, even as his brain turns upon itself, revealing to his soul a similar ending.

“Come with me,” says the man. “I know a place nearby that sells a lip-smacking pothu roast.”

Clutching the trophy and balancing the oar, Roopchand hops on the back seat of the scooter. The salty and warm wind whips against his hair as he courses toward another ending.

Host Commentary

Once again, that was A Series of Endings, by Amal Singh.

The author has this to say about the story: I wanted to do something interesting with story structure. I happened to read Haruki Murakami’s “Hard Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World” which, inexplicably, pivots between a traditional fantasy setting and a dystopian SF setting, and it all only makes sense only at the end, while still remaining largely ambiguous. It all spawned from there.

It’s easy to imagine life as a series of branching choices that lead to new choices, those paths extending out into an apparent infinity of possibility that will nonetheless have a finite conclusion. Humans, I think, are fascinated with that sense of possibility and potential for many reasons, not least of which is an inherent thirst for experiences beyond our own limited lives. I love how this story delves into the mundane and the mystical, the scientific and the spectacular, giving us a glimpse into not just a single incident in a single life, but a series of cascading moments and encounters and, yes, endings. But, as the prophet said, every new beginning comes from some other beginning’s end.

Escape Pod is part of the Escape Artists Foundation, a 501(c)(3) non-profit, and this episode is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license. Don’t change it. Don’t sell it. Please do share it.

If you’d like to support Escape Pod, please rate or review us on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or your favorite app. We are 100% audience supported, and we count on your donations to keep the lights on and the servers humming. You can now donate via four different platforms. On Patreon and Ko-Fi, search for Escape Artists. On Twitch, we’re at EAPodcasts. You can also use Paypal through our website, escapepod.org. Patreon subscribers have access to exclusive merchandise and can be automatically added to our Discord, where they can chat with other fans as well as our staff members.

Our opening and closing music is by daikaiju at daikaiju.org.

And our closing quotation this week is from Kurt Vonnegut, who said, “What we love in our books are the depths of many marvelous moments seen all at one time.”

Thanks for joining us, and may your escape pod be fully stocked with stories.

About the Author

Amal Singh

Amal Singh is an author from Mumbai, India. His short fiction has appeared in venues such as F&SF, Clarkesworld, Apex, Fantasy, and has been longlisted for the BSFA Award.

About the Narrator

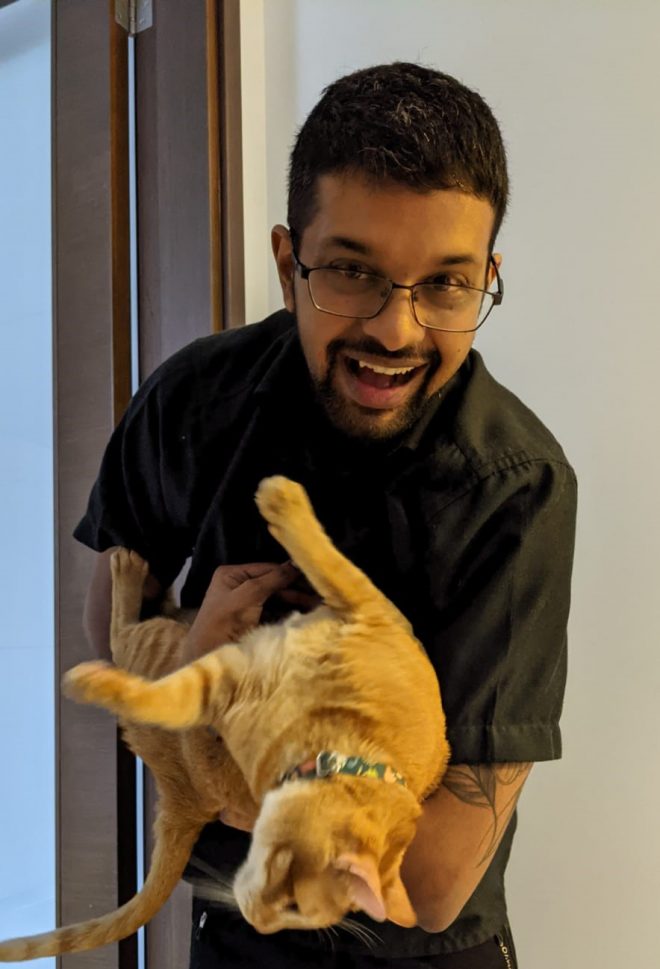

Kaushik Narasimhan

Kaushik is a management consultant by day and moonlights as a one man band with a variety of instruments and an electric guitar. He also enjoys writing, reading and listening to speculative fiction. He runs a flash fiction podcast called unseenfiction.com with a friend – short speculative fiction from South Asia.